his week Eisai and Biogen

announced

the results of their clinical trial of Lecanemab, another monoclonal

antibody against β-amyloid intended to treat Alzheimer's disease.

his week Eisai and Biogen

announced

the results of their clinical trial of Lecanemab, another monoclonal

antibody against β-amyloid intended to treat Alzheimer's disease.

Both Science and Nature magazines had articles on the story. Science focused on the fact that Eisai included 25% blacks and Hispanics, making it more “diverse.” Nature focused on the controversy, quoting Rob Howard of UC London as saying the claimed improvement in CDR-SB is a “really tiny and almost unnoticeable difference from placebo.”

Both articles missed the most interesting point of this study: the results are virtually identical to the ones in Biogen's first trial (which they called Emerge) of aducanumab. It's possible that this is just a coincidence, but it could also be telling us something significant about the role of β-amyloid in AD.

Eisai says the patients' scores in the CDR-SB cognitive test were changed by −0.45 in the intent-to-treat population. This, they say, is statistically significant at a level of p=0.00005. They also say the CDR-SB scores were significant at p<0.01 at all time points starting at six months.

What is the CDR-SB?

CDR-SB means Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes. It uses an 18-point scale based on interviews with the patients' carers and the patients.

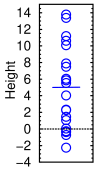

Heights of twenty people measured with a ruler of the same precision as CDR-SB

Suppose you measured the height of 20 people. Their average height is 5 feet. If the standard deviation was also 5, you'd get results like those shown in the graph at right. Some would come out as −2′ 3″, and some as 13′ 9″. To have a 50% chance of seeing a significant change, you'd have to measure 325 people.

Unlike most other cognitive tests, the CDR-SB mixes subjective impressions of carers with semi-objective facts. However, some researchers have praised it (although it's hard to be sure, as most articles on the topic are in Alzheimer's & Dementia, which is behind a steep paywall, so my university library doesn't subscribe to them).

Each question has five boxes. For example, the clinician might check the box for 0 for “independent function at usual level in job, shopping, volunteer, and social groups,” 0.5 for slightly impaired, and 1, 2, or 3 for increasing levels of impairment. The total score, as you probably guessed, is calculated by adding up the scores. It ranges from 0 to 18 and the test is claimed to have predictive value for people who are later diagnosed with AD or some other dementia.

Typical scores are 0.11 ± 0.23 for healthy patients, 1.29 ± 0.85 for mild cognitive impairment, and 5.01 ± 1.58 for Alzheimer's.[1]

Here is a sample CDR-SB test. A typical question is

How often does he/she know the exact date of the month?

o Usually

o Sometimes

o Rarely

o Don't know

What's the difference between “sometimes” and “usually”? Who knows, but if they tried to actually measure it, they'd have to ask the patient a hundred times. It would change the result and the patient would get bored and complain.

The unreliability of interview-style tests is, of course, well understood, and indeed Eisai also measured ADAS-cog14, ADCOMS, and ADAS-MCI-ADL. They say “key secondary endpoints” were significant at 18 months, not at earlier times. Granted, I'm engaging in Kremlinology here, but 'key' looks like a weasel word to me: are there other secondary endpoints that weren't significant they're not telling us about? (Who am I kidding, this is Big Pharma, of course there are!)

A good discussion of the minimum clinically important difference is found in the paper by Borland et al.[2]. These authors consider a change of ≥0.5 points in CDR-SB to represent a clinically meaningful change. This means the Eisai results are not clinically meaningful.

Borland et al. also found that CDR-SB scores don't correlate with other tests in prodromal stages, with coefficients of correlation between −0.2 to +0.6. This is, for want of a better word, terrible. We observed a similar lack of consistency in our drug trial among ADAS-Cog, MMSE, and some other tests on patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's. This happened in the Emerge trial as well: MMSE scores had a p-value of 0.049 (borderline significant), ADAS-Cog 13 had a p-value of 0.010, and ADCS-ADL-MCI was significant at p<0.001. So is the result real or not? There is no way to tell.

Comparison with Biogen's Aducanumab trials

Let's compare these results with Biogen's earlier trials (from [3]). The green entries are the net improvement that we're interested in. The numbers in gray were calculated from the press release.

| Parameter | Lecanemab | Aducanumab EMERGE |

Aducanumab ENGAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change in CDR-SB (AD) | +1.21 | +1.35 | +1.59 |

| Change in CDR-SB (Plac) | +1.66 | +1.74 | +1.56 |

| AD − Placebo | −0.45 | −0.39 | +0.03 |

| % Improvement in CDR-SB* | +27 | +22 | −2 |

| No. patients treated | 897 | 547 | 555 |

| Weeks of treatment | 78 | 78 | 78 |

| p-value | 0.00005 | 0.012 | 0.833 |

| ARIA-E + ARIA-H (%) | 21.3 | 35.0 | 36.0 |

This table shows that the effects for Lecanemab were almost identical to the first Aducanumab trial (−0.45 vs −0.39). Stated another way, there was about 5% more improvement in the new trial compared to the old one (27% vs 22%). The better statistics were almost entirely due to the higher number of patients treated (64% more patients).

Is there a pattern here? In two trials, the antibody seemed to reduce the rate of decline by one-fifth to one-fourth. If AD were multifactorial, and if β-amyloid accounted for one fourth of the total pathology, it might explain this coincidence. However, there's also huge noise in these results: the Engage trial found no effect at all. In science, one bad experiment can ruin a dozen good ones, which is why it's so tempting to throw it out.

What does it really tell us?

The p value of 0.00005 might look suspiciously small, but in all likelihood it's a function of the non-parametric nature of the test. Any test that involves patient caregivers is subject to groupthink, as they can easily share stories over coffee and convince each other that the patient is much better. If they all decided the patient forgot things “sometimes” instead of "usually" it would improve the statistics enormously.

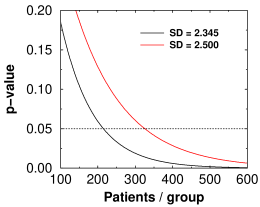

Theoretical p-value versus number of subjects for lecanemab (black curve) and aducanumab (red curve)

Whether a result reaches statistical significance depends critically on the accuracy, or to be precise the standard deviation, of the measurement used. In the Emerge trial, the SD for CDR-SB was closer to 2.500 (calculated from their numbers). For the Lecanemab trial, it was 2.345. The graph at right shows that to reach the same level of significance as the Eisai trial, the Emerge trial would have needed 1.5 times as many subjects per group as the Eisai trial, or 1362 subjects, or 2½ times as many as they had. That 6.6% decrease in SD is why Eisai's statistics are so much better. SD is the main factor in power analysis, which tells you how many patients you need. In the end, Biogen lost billions because their power analysis was based on an SD of 1.920 but they actually got something higher. (The baseline started out as 2.4 ± 1.01, so 1.92 probably seemed like a nice safe number.)

With high enough N, anything becomes significant. In the Engage trial, if there had been 47,950 subjects in each group they would have had statistical significance that Aducanumab makes AD 2% worse (SD = 2.37). That's why clinical significance is so important to consider.

Another thing that happens with Alzheimer's is that the sick patients suddenly seem to get better for no reason when treated, then get worse again. This seems to be a function of something novel occurring in their lives, such as having a giant needle jammed into their arm and being asked a lot of dumb questions. That's why what we really need to know are the survival times. And sometimes, the placebo patients don't stay sick like they're supposed to, which really screws up the results.

What does all this mean?

First and foremost, it tells us that anti-beta-amyloid therapy has hit a ceiling effect. Lecanemab hit significance mainly because they had 64% more patients, not because it was better. This means that getting every last molecule of beta-amyloid out of the brain is probably not going to do much more than slow the rate of progression by 25 or 30 percent.

It also tells us that the tests we're using to measure cognitive impairment are unreliable. Many groups, including Xu et al [1], are trying to find a more objective test. So far we don't have one. A similar phenomenon occurred in many of the Covid trials, where researchers substituted subjective evaluations for actual measurements and corrupted the results.

Maybe, as some people are saying, AD is multifactorial. Or maybe we need to give it earlier. Or maybe there are two populations: responders and non-responders. Or maybe there are two forms of the disease. But it's surprising that after all these years we still have no idea why Aβ is there. Everyone assumes it's caused by neuroinflammation and we have to get rid of it. The only good thing about the Lecanemab trial is that we now know that getting rid of Aβ is not going to cure AD.

[1] Xu X, Xu S, Han L, Yao X. Coupling analysis between functional and structural brain networks in Alzheimer's disease. Math Biosci Eng. 2022 Jun 20;19(9):8963-8974. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2022416. PMID: 35942744.

[2] Borland E, Edgar C, Stomrud E, Cullen N, Hansson O, Palmqvist S. Clinically Relevant Changes for Cognitive Outcomes in Preclinical and Prodromal Cognitive Stages: Implications for Clinical Alzheimer Trials. Neurology. 2022 Jul 14:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200817. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200817. PMID: 35835560.

[3] Budd Haeberlein S, Aisen PS, Barkhof F, Chalkias S, Chen T, Cohen S, Dent G, Hansson O, Harrison K, von Hehn C, Iwatsubo T, Mallinckrodt C, Mummery CJ, Muralidharan KK, Nestorov I, Nisenbaum L, Rajagovindan R, Skordos L, Tian Y, van Dyck CH, Vellas B, Wu S, Zhu Y, Sandrock A. Two Randomized Phase 3 Studies of Aducanumab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9(2):197-210. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2022.30. PMID: 35542991.

sep 30 2022, 7:56 pm. updated oct 01 2022, 9:40 am and oct 02 2022, 5:45 am graph added oct 05 2022, 4:34 am. last updated nov 18 2022, 6:29 am