ast week Genentech

reported

that crenezumab, an antibody against beta-amyloid, failed

to slow or prevent dementia in autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease.

ast week Genentech

reported

that crenezumab, an antibody against beta-amyloid, failed

to slow or prevent dementia in autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease.

The antibody was tested on 252 people who are members of a large extended family, two thirds of whom have the presenilin 1 E280A mutation. These patients automatically get symptoms of AD around age 44.

This isn't just some obscure clinical trial. It's estimated that as many as sixty million people will die from AD in the next fifty years, and this trial shows that we have been on the wrong track from the beginning.

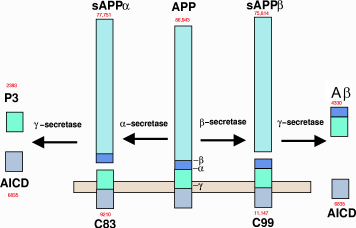

Metabolism of amyloid precursor protein to produce beta-amyloid

Until now, even beta-amyloid skeptics were convinced that familial early-onset AD had to be caused by beta-amyloid, called Aβ for short. Complete data of the study are not available yet, but one thing was clear from the beginning: if Aβ was the sole cause of the disease, then removing it would slow disease progression no matter how early it was administered. Biogen's Aduhelm (aducanumab) trial showed convincingly that eliminating Aβ oligomers from sporadic, or late-onset AD, had no effect. We now know that eliminating Aβ from early-onset AD also has no effect.

Why is everybody picking on beta-amyloid?

The Aβ hypothesis is one of those ideas that just will not die.

Presenilin 1, the focus of Genentech's trial, is a protease enzyme, part of a big enzyme complex called gamma-secretase. It's essential for producing Aβ. The idea was that presenilin mutations produced the more toxic form Aβ42 instead of the comparatively harmless Aβ40.

Aβ42, the “bad” form of Aβ, spontaneously aggregates into clumps called oligomers. It was hoped that getting rid of these clumps would stop the progression of the disease. The Genentech and Biogen antibodies both specifically recognized these clumps and got rid of them.

Just last month in an article in Frontiers in Neuroscience[1] four authors from Acumen Pharmaceuticals wrote this:

Research over the past three decades has established a clear causal linkage between AD and elevated brain levels of amyloid β (Aβ) peptide, and substantial evidence now implicates soluble, non-fibrillar Aβ oligomers (AβOs) as the molecular assemblies directly responsible for AD-associated memory and cognitive failure and accompanying progressive neurodegeneration.

Reading that paragraph, you might reasonably ask: The problem is solved. What more is left to test? Unfortunately, inhibiting beta-secretase and gamma-secretase, the two enzymes responsible for manufacturing Aβ, has no effect; getting rid of Aβ has no effect; and in vitro studies still have not converged on a convincing mechanism.

So why did people believe it? You can kill cultured neurons by putting Aβ oligomers on them. And transgenic mice engineered to produce large amounts of Aβ in their brains become neurologically and cognitively impaired. These results led us down the wrong path.

Then there was the finding that Aβ was found in the plaques that are found in the disease. Unfortunately, it was soon found that the amyloid plaques didn't correlate with cognitive impairment.

The biggest thing that made that garden path so appealing was the similarity with familial amyloidoses, which are inherited diseases in which a mutated protein gets deposited as a filamentous beta-sheet in tissues outside the brain, causing peripheral neuropathy. The most common one is transthyretin, aka prealbumin. There are over 100 variants of the transthyretin gene that cause peripheral amyloidosis. There are other types of familial amyloid neuropathies, caused by mutations in other proteins such as gelsolin. One neurology textbook classifies them as the Portuguese type, the Swiss type (which is one cause of carpal tunnel syndrome), the Iowa type, and the Finnish type, which begins with corneal lattice dystrophy in the eye that eventually spreads to cause peripheral neuropathy, skin folding, and facial paresis. These disorders cause various amounts of muscle weakness, numbness, paresthesias, or pain and difficulty walking. They typically start between age 25 and 35 with death occurring 10 to 15 years later.

Despite the name, none of the disorders has any relationship to AD. But when Aβ was discovered in plaques, it made perfect sense that AD would turn out to be another amyloidosis.

Safe science is pathological science

Philosophers of science talk about paradigm shifts and how scientists tend to adhere to a theory until it is no longer tenable. But the reality is that modern science is held back by the need to be safe: safe for patients, safe for researchers, and most of all safe for their employers.

The quote from the Frontiers article, with its absence of nuance and claims of near-certainty, is a perfect recitation of the path that has been designated as safe for researchers to follow. New investigators recognize it as a safe option and imagine new ways to build on it. And Big Pharma, whose stockholders care only about the safety of their investments, spends billions testing drugs based on it.

It's only natural for people to subsume their interest in the truth to career survival. Those who don't will lose funding, find themselves being publicly ridiculed, and quickly become unemployed. If you're unemployed, you can't cure anything at all. Just try setting up a lab in your basement: within a week you'd have ten guys with blue windbreakers with DEA printed in big yellow letters on the back smashing down your front door.

Industry labs, at least those in big companies, have equipment that academics can only dream about. If an industry researcher needs a half-million-dollar piece of equipment, one phone call later it shows up along with a guy who takes it out of the box, plugs it in for them, shows them how to push the Start button, and takes away all those little styrofoam peanuts. But if you ask anyone in industry you'll find that they are adamant that doing research is not their job.

Academic scientists have to spend their time writing grants, teaching students, attending meetings, and writing papers. Their job is not to find cures for diseases. Their job—and it's a tough one—is to remain employed while making do with equipment that they know will never be able to provide the answers they need. Worse, in academia there are so many hostile reviewers eager to nail your career over a bad gel that everyone does defensive science.

I would probably never survive in industry: within five minutes I'd have calmly and patiently explained to them why their product will never work. Within ten minutes I'd be out on the corner holding a cardboard box.

But if industry had taken those billions and done the research academia can't do, they'd probably have a product that cures the disease by now.

Being safe produces solutions to things that are not really problems, and presents ideas as consensus opinion and therefore designated as safe, but are scientifically dead wrong. This is pathological science: not evil, mad scientists torturing bunnies but ordinary people whose primary concern is to stay employed in a system that is designed not to take risks. Result: billions of dollars wasted solving problems that are not real.

[1] Krafft GA, Jerecic J, Siemers E, Cline EN. ACU193: An Immunotherapeutic Poised to Test the Amyloid β Oligomer Hypothesis of Alzheimer's Disease. Front Neurosci. 2022 Apr 26;16:848215. doi: 10.338 9/fnins.2022.848215. PMID: 35557606; PMCID: PMC9088393.

jun 25 2022, 5:33 am