he idea that economic inequality is a form of social injustice has become widely

accepted by sociologists and certain politicians. Recently, the idea has started

showing up in mainstream science journals[1]. So it's a good time to ask:

is there any validity to it?

he idea that economic inequality is a form of social injustice has become widely

accepted by sociologists and certain politicians. Recently, the idea has started

showing up in mainstream science journals[1]. So it's a good time to ask:

is there any validity to it?

There's an enormous practical difference between eliminating poverty and eliminating inequality. The former can be done through economic growth. The latter would require radical restructuring of our economy and government redistribution of income to make everyone equal. The literature is full of people equivocating between the two, for instance by talking about how poor people become obese because their diet is worse. This is poverty, not inequality, but sociologists often mix them together.

It's critical to maintain the distinction. If economic inequality really caused all the problems attributed to it, such as reduced life expectancy, teenage births, imprisonment, obesity, homicides, and “distrust”, then we would have to admit that Piketty's solution, a global tax on wealth, might be necessary. What this means in practical terms is for the government to help itself to your bank account, take whatever it wants, and distribute it to those who have less. Such a policy, if it could be implemented, would devastate economic growth.

When we look at what sociologists are saying, we have to avoid openly socialist sources like Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century and focus only on data-driven sources. In Part 1 I discussed how the World Bank's Gini coefficient, which is a measure of economic inequality, contradicts some of the commonly accepted conclusions about inequality. Here I focus on the data published in The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett. (I'll refer to this as TSL.)

Although TSL is already eight years old, its conclusions have been widely cited (see ref. [1] for example) and repeated in many subsequent papers, so it is a good place to start.

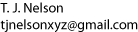

Fig. 1. Life expectancy vs national income (redrawn from [2], approximate curve added).

TSL starts out by showing that poor countries have poorer health, as shown by life expectancy, up to about $20,000/year income, after which the curve levels off (Fig. 1). This is because the parameter is limited by biology. Most of the other parameters, such as obesity and teenage births, are similarly limited, so they would follow a similar curve.

Most of the subsequent analysis in TSL talks about 21 rich countries in the right side of this curve. I still have not been able to find out why these 21 were selected and not, say, the 34 in the OECD. But never mind. Among these 21 countries stuffed with rich bastards, the authors claim that those with higher “inequality” have more health problems than those with lower economic inequality.

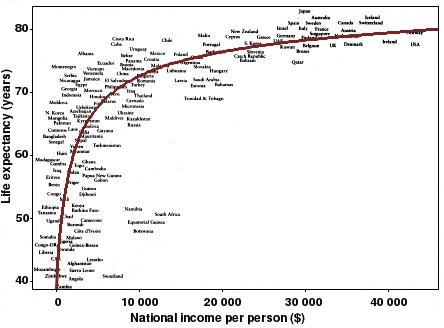

Fig. 2. Income inequality in different countries (redrawn from [2] and [3]). The authors say the ‘index’ reflects life expectancy, mental illness, obesity, infant mortality, teenage births, homicides, imprisonment, educational attainment, distrust and social mobility.

The lack of numbers on this graph means that no conclusions can be drawn from it, yet it has been widely reproduced.

Maybe you can see the problem already.

Let's assume the hypothetical perfect case where all the countries have the same mean income. Even if one compares rich countries alone, it is obvious that countries with “inequality” will have a greater percentage of citizens in the left-hand region of the curve. For example, if 10% of the population in country A but only 5% of country B (a country with less inequality) falls in the left part of Fig. 1, then A will have more poor people and therefore a higher index of health and social problems, even though they have identical mean incomes. Thus economically ‘unequal’ societies have more problems because they have more poor people. Despite what the sociologists claim, the problem in these societies is not inequality, but poverty.

This might sound obvious, but sociologists are beavering away to convince us that the problems they allude to are not the result of more poor people, but are caused by stress that's produced at discovering that there is such a thing as rich people. For instance, they claim that poor people in the USA are fat not because they buy cheap food rich in fat and carbohydrates, but because they're stressed out by their knowledge that someone, somewhere, has a higher salary than they do. Among people already inclined to believe that government intervention in the economy is invariably beneficial, this is an appealing argument. But they also have to convince the rest of us.

One trick they use is to expand the y-axis: if you started it at zero, the line would appear nearly horizontal. Expanding it is easy to do if you omit the axis numbers and simply label them ‘Better’ and ‘Worse’ (see Fig. 2). Another trick is to drop the word ‘economic’, conflating income differences with inequality caused by unfair treatment.

The authors of TSL use both tricks. Some of their graphs are labeled, some aren't; some do start at zero, while others span a narrow range. In their graph of homicide rates vs economic inequality (p. 135), there is clearly no statistical correlation unless one includes the USA, which shoots, so to speak, off the chart. The reason is well understood: there are distinct populations in the USA, not present in Japan and Sweden, that are noted for being violent. There are also cultural differences about firearms which have nothing to do with inequality.

These differences cannot simply be dismissed as ‘racism’ and prejudice, as the authors of TSL do. There are real, live social pathologies going on here. The takeover of sociology by politically charged ideas like racism is producing an intellectual desert that makes finding deeper causes nearly impossible.

Even when the correlations are significant, as some appear to be, we don't have to inquire about the mechanism. The mechanism is clear: regardless of whether counties, states, or countries are being considered, in ‘unequal’ societies, a larger portion of the population is shifted into the left of the curve of Fig. 1, which is to say it has more poor people. The data analysis confounds economic inequality with poverty, and an unambiguous conclusion cannot be drawn from it.

The authors of TSL write: “[R]educing [economic] inequality would increase the wellbeing [sic] and quality of life for all of us.” We cannot conclude that from their data. The entire case for inequality instead of poverty being the cause of social problems rests on faulty data analysis. The question of how stratification could cause stress, which the authors claim as a mechanism, is also on shaky ground: if there is a correlation, surely expectations and envy play a major role, and we would be better off questioning whether such envy is really justified.

As with many papers that I've seen on the subject, the authors start out by talking about inequality, then equivocate back and forth with poverty. The two things are totally different, both in their meaning and in their possible solutions. Until sociologists find a way to orthogonalize their variables, we cannot conclude that inequality is a problem.

1. Payne KB, Brown-Iannuzzi JL, Hannay JW (2017). Economic inequality increases risk taking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(18), 4643–4648. Link

2. Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE (2009). The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. London: Penguin.

3. Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. (2015). Income inequality and health: A causal review. Soc. Sci. Med 128, 316–326.

Created may 21, 2017; last edited may 23, 2017, 9:18 am