've been looking at houses this month. Around

here, all the houses have the same boarded-up-no-more-kids-and-never-had-'em ambiance.

In one, some elderly women had set up a baby room, with toys and baby stuff, complete

in all respects except for an actual baby. In another, only one bedroom had ever been

occupied. The other bedroom had only an old-fashioned fainting couch. The emptiness of

the owner's life permeated the space.

've been looking at houses this month. Around

here, all the houses have the same boarded-up-no-more-kids-and-never-had-'em ambiance.

In one, some elderly women had set up a baby room, with toys and baby stuff, complete

in all respects except for an actual baby. In another, only one bedroom had ever been

occupied. The other bedroom had only an old-fashioned fainting couch. The emptiness of

the owner's life permeated the space.

The window from her dining room, where she would, I imagined, sit with her cup of coffee watching the rain, looked out over power lines that resembled empty clotheslines. She'd set up a covered patio with a hammock and a TV, surrounded by a six-foot privacy fence. The loneliness was overpowering; I visualized a lady lying in the hammock reading some transgressive novel, then putting the book down and thinking sadly about how life could have been different, if only.

For sale, cozy bungalow, 1br, free pets provided. Skylight, backs to woods. Must see to believe! Hurry, this one won't last!

Even my real estate agent, the guy who drove me twenty miles down a pothole-filled road to show me a rotting A-frame next to a junkyard and a trailer (or would have shown me, if he'd been able to get the door open), couldn't get out of there fast enough. But it left me wondering why humans in advanced civilizations seem to be driving themselves toward extinction.

We can get some answers by looking at other species. A recent article[1] in PLoS One written by four French researchers concludes that a 4% decline in the fertility rate would have been enough to wipe out the Neanderthals. Question: Is this realistic? And what does this portend for us, now that our fertility rates have declined by over ten times this amount?

The authors ran computer simulations of three populations (Eastern, Southern, and Northern Europe). The Eastern population would have migrated westward because it had low population density, while the Northern population would have migrated south, perhaps to vacation in Benidorm, which is consistent with the fact that southern Neanderthals lasted the longest.

The authors set the overall adult fertility rate to 0.27 and varied the fertility rate for young females. They found that, for all three populations, reducing that number from 0.1415 to 0.1376 caused the population to fall below the threshold of 5,000 individuals within 10,000 years. This is known as the minimum viable population or MVP, below which extinction is certain. Lowering the rate to 0.1300 (a decrease of 8%) caused extinction in 4,000 years.

The paper is a bit confusing, with fertility rates expressed in non-standard units and different parameters mixed together in their tables without clear explanation. Moreover, their own results confound the main finding: by reducing the population survival rate from 0.7171 to 0.6850, extinction happens in 20 years instead of 6,000. Thus, their conclusion is that, really, just about anything could have happened, but it's not necessary to invoke catastrophes such as volcanoes, diseases, or war; demographic change is enough.

Many studies have shown that one of the first effects of environmental stresses in large mammals, such as increased population density or decreased food resources, is a reduction in fertility. Stated another way, for long-living species like hominids, juvenile survival has a smaller effect on the population growth rate than adult survival.[2] So their hypothesis is that food stress reduced the amount of stored body fat in primiparous females (i.e., women having their first child), leading to demographic extinction.

What does it say about us? Ten years ago, if I said that humans are on a path to extinction, people would have called me crazy (and I suppose some of them still do). Are there not over seven billion humans? Do we not suffer from overpopulation?

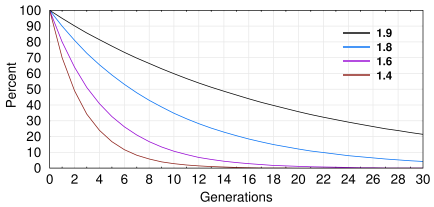

Graph of population vs time at various fertility rates. This simplified calculation assumes no infant mortality or age-dependent demographics. A fertility rate of 2.1 is needed for stability. At a fertility rate of 1.4, it takes only two generations for the population to drop by half.

What no one wants to admit is that the enlightenment ideal of equality has run up against the cruel reality of mathematics and statistics. Statistics may not be fun to think about, but a statistic can nail us whether we face it or not.

In the 1960s the common belief was that overpopulation is a threat. But birth rates in industrialized countries have now declined to dangerous levels. People search for easy explanations: maybe there's a pollutant, and all that's needed is a big new government program to remove it. Or maybe it doesn't matter if the population drops. Or maybe science will save us.

Maybe it will, but the general feeling among scientists is that if the decline is a side-effect of women delaying childbirth, as it appears to be, then it's a social problem, not a scientific one, and science has no role to play.

In fact, it does: fertility rates are almost certainly baked into our psychological programming in ways we don't understand. Why do women suddenly decide en masse to stop having children, and what conditions in advanced societies encourage this?

Social psychology cannot yet answer these questions. Until this branch of science can throw off its ideological baggage and begin developing testable theories, science can only provide an unhappy choice: create replacements using IVF and incubators, or wait for natural selection to do what nature does.

Positive feedback loops, and negative feedback loops like this one, where social change interacts with genetics to cancel itself out, are one way our social structures get irreversibly imprinted on our genes. That happens whether we're aware of it or not. We urgently need a better scientific understanding of how social trends interact with genetics.

It would also be nice if we were allowed to talk about it. Who knows, it might turn out to be important.

1. Degioanni A, Bonenfant C, Cabut S, Condemi S (2019). Living on the edge: was demographic weakness the cause of Neanderthal demise? PLoS One 14(5): e0216721 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216742 Link

2. Pfister CA. Patterns of variance in stage-structured populations: Evolutionary predictions and ecological implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998; 95: 213\u2013218. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.1.213 PMID: 9419355

jun 08 2019, 5:54 am. last edited jun 14 2019, 5:02 pm