've always wanted to give a course titled Bad Clinical Trials. There's a vast

amount of material to work with, like that psychiatrist

a few years back who thought taking LSD would be a good way to get in touch with his

patients' mental state. But Dangerous Clinical Trials, when bad things happen

to the clinical staff, might be more entertaining to the students.

've always wanted to give a course titled Bad Clinical Trials. There's a vast

amount of material to work with, like that psychiatrist

a few years back who thought taking LSD would be a good way to get in touch with his

patients' mental state. But Dangerous Clinical Trials, when bad things happen

to the clinical staff, might be more entertaining to the students.

A biologist once told me that the anti-Alzheimer drug they were getting ready to test was turning her rats vicious. Lab rats are bred to be tame and easy to handle, but she called me up one day asking whether, by any chance, I happened to know anything about rat bite fever. It turned out that the drug, supposedly a cognitive enhancer, was actually producing a mild case of mania, which made the rats hyper-aggressive. After a while, all the research assistants, their fingers no doubt covered in Band-Aids, threatened to quit rather than continue with this drug.

Broken bones, concussions, and smashed teeth can happen in a fall, especially in a trial with aged patients. Dementia causes psychosis, and patients lose control of their bodily functions, which makes their caregivers' job more difficult. But even in trials of varenicline, an anti-smoking drug, there were ten cases of assault and nine cases of homicidal ideation (death threats)[1]. According to the FDA's Medwatch adverse event reporting log, escitalopram, an anti-anxiety drug given to children, caused four death threats during testing, though no actual homicides were mentioned. Perhaps a certain amount of anxiety is a good thing.

Regardless of whether the patient vomits, gets a headache, or threatens the doctor, these are called adverse events or AEs. Enough serious AEs, and the drug gets dropped. They have a huge cost: 40–70% of promising new drugs never even make it to clinical trials because of the chance they might cause fatal cardiac arrhythmia in patients with a rare mutation in a protein called hERG (aka Kv11.1).

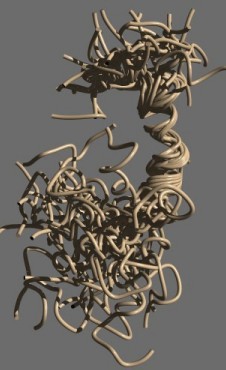

Molecular model of beta-amyloid, showing 30 superimposed conformations (based on [6])

Am I at risk for Alzheimer's disease?

I hear this question all the time, especially from people who've discovered they carry the ApoE ε4 allele. If you're carrying two of them, it increases your risk of getting late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD) by 12-fold. Until now, all I could say was it's not a guarantee, and worrying would only make it worse. Live life while you can. Oh, and mind that bus.

There are some things we can say. Age 65 is the cutoff point. If none of your relatives got AD before age 65, you're very unlikely to get the early onset form. This means any memory loss you experience before hitting 65 is almost certainly due to something else. But what about late onset AD, which is the most common form, and which occurs after age 65?

This is where your ApoE genotype makes a big difference. But there are other predisposing factors as well. For example, over 80% of AD patients have a history of at least one neuropsychiatric symptom.[2] Burke et al.[3] looked at NPI-Q tests, which compile an “inventory” of them, and found that people with chronic delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, elation, apathy, and similar symptoms were at higher risk for later AD. So if you don't have those symptoms, there's hope, even if you have the ε4 polymorphism.

Unfortunately, it's the nature of science to overturn past dogma. That means tomorrow a study could come out claiming that delusions protect you.

Does aspirin protect against Alzheimer's or not?

Another dogma, held for years, is that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs, like aspirin, have no benefit for AD. But a recent article in PLoS One[4] says they do. They took 5,072 patients and divided them into two groups. One group said they were taking an NSAID, mainly aspirin, and the other group said they weren't. After 12.7 years, the authors found that the risk of death from AD in the aspirin group was reduced by 71 percent.

The result was statistically significant at p=0.009. But people often take daily aspirin because of other life-threatening conditions. And indeed, the co-morbidity index showed that more of the patients on aspirin died of stroke, heart disease, and other causes. This result was highly significant, p=0.001. It seems the aspirin patients weren't taking it just for fun, but because they knew something.

You can see how misleading the result would be by imagining if you gave cyanide to the patients: none of them would die from the disease. A 100% effective preventative cure! Another possibility is that the ones who didn't report taking aspirin were already in the early stages of AD and simply forgot.

A lot of research says that astrocytes, small cells in the brain that are supposed to protect and nurture our neurons, can kill cells that are infected with certain viruses. This is important: it's what CD8+ T cells, which are important components of the immune system, do in the periphery. T cells are found in the brain, but they don't proliferate there—they have to come from the periphery and cross the blood-brain or blood-CSF barrier. Could it be that astrocytes are taking over their task? If so, what is different about a neuron in an AD patient that induces astrocytes to attack it? Maybe the “bad tau” theory isn't so crazy after all.

The aspirin finding, if true, is consistent with the idea that inflammation is a major contributor to the pathology in AD and that beta-amyloid is produced, at least in part, as a defense against inflammation.

Alzheimer's disease and gingivitis

Another paper[5] found that Porphyromonas gingivalis, a bacterium that causes gingivitis, is much higher in the brains of patients who died of AD than in patients who died of other things. These authors speculated that gingivitis triggers microglial inflammation, and that amyloid plaques are made to seal off the inflammatory stimulus. This paper has journalists talking about how you should floss every day to prevent AD.

It would be great if people did that, but just like the aspirin result, it points out a common problem: you can never rely on what patients tell you, or what they forget to say.

It's likely that Alzheimer patients would forget to floss or find themselves unable to handle the muscle coordination that's required. So if their caregivers don't floss them, it probably doesn't happen. No wonder they have gingivitis.

People with dementia have an awful time. I knew one stroke victim who was delirious, yelling and screaming all day and night in his hospital bed. That poor human being was permanently trapped in a nightmarish twilight world, unaware of where he was or what had happened to him. Another guy in the next room kept talking about how he wanted to die. It's enough to make patients in nearby beds pray to God thanking him that they only have cancer.

It might seem odd: those times when a person suffered and struggled the most while young are among their most treasured memories when they are old, and the ones they most fear to lose. Emotions, pleasant or unpleasant, tie us to the world and to places. Our memories of them make us who we are. Dementia takes all of that away.

1. Moore TJ, Glenmullen J, Furberg CD. (2010). Thoughts and acts of aggression/violence toward others reported in association with varenicline. Ann Pharmacother. 44(9),1389–1394. PMID: 20647416 DOI: 10.1345/aph.1P172 Link

2. Zhao QF, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, Xu W, Li JQ, Wang J, Lai TJ, Yu JT. (2016). The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 190, 264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069. PMID: 26540080 Link

3. Burke SL, Maramaldi P, Cadet T, Kukull W4. (2016). Neuropsychiatric symptoms and Apolipoprotein E: Associations with eventual Alzheimer's disease development. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 65, 231–238. PMID: 27111252 PMCID: PMC5029123 DOI: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.04.006

4. Benito-León J, Contador I, Vega S, Villarejo-Galende A, Bermejo-Pareja F. (2019). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs use in older adults decreases risk of Alzheimer's disease mortality. PLoS One. 14(9),e0222505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222505. PMID: 31527913 Link

5. Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, Benedyk M, Marczyk A, Konradi A, Nguyen M, Haditsch U, Raha D, Griffin C, Holsinger LJ, Arastu-Kapur S, Kaba S, Lee A, Ryder MI, Potempa B, Mydel P, Hellvard A, Adamowicz K, Hasturk H, Walker GD, Reynolds EC, Faull RLM, Curtis MA, Dragunow M, Potempa J. (2019). Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer's disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv. 5(1):eaau3333. PMID: 30746447 PMCID: PMC6357742 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aau3333

6. Tomaselli S, Esposito V, Vangone P, van Nuland NA, Bonvin AM, Guerrini R, Tancredi T, Temussi PA, Picone D. (2006). The alpha-to-beta conformational transition of Alzheimer's Abeta-(1-42) peptide in aqueous media is reversible: a step by step conformational analysis suggests the location of beta conformation seeding. Chembiochem. 7(2), 257–267.

sep 28 2019, 1:18 pm. edited sep 29, 6:29 pm