he Brits have a saying: you wait twenty minutes for a bus, and then three of

them show up. That's what's happening now for those of us looking for clues about

Alzheimer's disease.

he Brits have a saying: you wait twenty minutes for a bus, and then three of

them show up. That's what's happening now for those of us looking for clues about

Alzheimer's disease.

The latest clue is social isolation and loneliness. A recent paper using data from the Mexican Health and Aging Study of 10,905 Mexicans showed that parents of adult children who migrated to the USA have increased risk for a number of conditions, including hypertension, coronary heart disease, depression, and dementia.[1] The researchers found a steep decline in immediate and delayed recall when subjects were tested 9 to 11 years after their child moved away.

This was true only for women, who are known to be at higher risk for AD than men. The authors speculated that the men were employed and obtained adequate social contact from their jobs, while the women were more homebound and isolated.

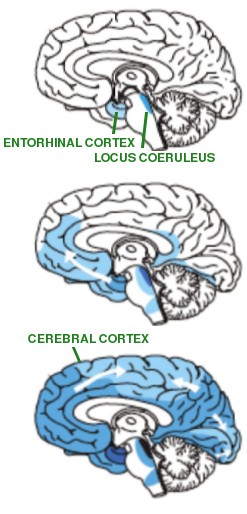

Alzheimer's starts in the locus coeruleus, which produces norepinephrine in the brain, and the transentorhinal cortex, which is important in spatial memory consolidation and object identification. Alzheimer pathology then spreads to the hippocampus and the cerebral cortex. Diagram from Fornari et al. [6], cited via Creative Commons Attribution License

Then last October another study came out[2] in which the researchers asked 1,905 Swedish patients one question: do you often feel lonely? Over the next twenty years, 13.4% of those who answered ‘No’ developed Alzheimer's disease, while 27.8% who answered ‘Yes’ developed it. Total (all-cause) dementia also increased, from 26.7% to 48.1%. Both were highly significant at p<0.001. By contrast, vascular dementia only increased from 10.0% to 15.8%, which was not statistically significant. Alcohol and smoking were also measured and found not to correlate with AD, but depression was: 13.9% of those with CES-D scores ≤ 15, (not depressed), developed AD, while 19.1% of those with CES-D scores above 16 (= depressed) got AD.

Depression

What could be going on? Depression is a prominent feature in AD, and there's now a big literature saying that it might be a contributing factor to the disease and just an effect of it. Maybe it's related to parts of the brain that involve talking and interacting with other humans, but no one really knows.

Even transgenic 5xFAD mice, which are used so often as a model for familial early-onset AD that they've become really cheap, show an earlier onset of AD-like symptoms after 2–3 months of isolation stress.[3] Giving the mice above-normal levels of environmental enrichment, including crinkly paper to chew up, pieces of PVC tubing to crawl through, and running wheels, didn't help, suggesting that it was the social isolation, not the lack of mental stimulation or physical exercise, that was at fault. Beta-amyloid levels weren't affected by isolation or enriched environment. This isn't surprising, since these mice are engineered to produce very high levels of beta-amyloid. But paradoxically, amyloid plaques were increased by about 50%, as was BACE1, the enzyme that makes beta-amyloid. This means that more beta-amyloid was indeed being made, but it was rapidly being converted to amyloid plaques.

There are countless anecdotal stories about people in a low-stress environment who reported their brains “turning to mush” due to a lack of human interaction. It might be interesting to compare different personality types or ethnicities: Italians and Chinese people seem to be highly dependent on intense social interactions (the latter to such an extent that non-speakers often mistake a casual conversation for a heated argument), while more northern types can tolerate solitude. Would extroverts, Italians, and Chinese people be more susceptible to AD when they're socially isolated than introverts? We don't know the answer.

What is the role of beta amyloid?

How does beta-amyloid fit in? A 2011 study in Nature Neuroscience claimed that neuronal activity increased beta-amyloid levels in the interstitial fluid, which is the space between cells where beta-amyloid is released after it's made.[4] We need to be cautious about interpreting this result, because there's always a tendency to cram the “beta-amyloid = bad protein” theory into these kinds of results. Indeed, when researchers found that neuronal activity increased beta-amyloid release, while regions with high neuronal activity were unaffected by amyloid plaques[5] some people dismissed it as a contradiction. But other researchers now think beta-amyloid has an important function in synaptic vesicle formation, which is to say it's important for memory and brain function. And there's good evidence that BACE1, the enzyme that makes it, is critical for that.

Other theoriesPost-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): In PTSD the locus coeruleus becomes overactivated, causing hyper-responsiveness. The locus coeruleus is an alerting system for stress, and it is the earliest brain region affected in AD. PTSD sufferers have a higher incidence of AD.

Infection: A variety of viruses and bacteria are associated with AD. Inflammation is a feature of AD, suggesting that the brain's immune system has somehow gone haywire in AD. One possibility is that intestinal bacteria are doing something. There's now strong evidence this happens in Parkinson's disease.

Abnormal neuronal firing: Depression happens when neurons don't fire enough; epilepsy happens when they fire too much. Both occur in AD.

Even though BACE1 inhibitors like semagacestat wipe out beta-amyloid production, they make AD worse in clinical trials. In mice, when transgenic mice that were engineered to produce beta-amyloid were bred with mice lacking BACE1, their AD-like symptoms were abolished, but the new double-mutant mice now had bad memory deficits, defects of axon guidance, and schizophrenia-like behavior. The same result can be obtained pharmacologically: giving a BACE1 inhibitor to normal mice reduces the size of their dendritic spines and messes up their long-term potentiation (a model for memory).[5] This means that BACE1, once thought of as a bad enzyme whose only function is to produce toxic molecules like beta-amyloid, is actually essential for normal cognition and synaptic plasticity. Of course, more research is needed: BACE1 could be doing other things besides making beta-amyloid.

What can be done for isolated elderly patients? Many live alone and spend much of their day watching TV. I would certainly go mad if I had to do that (some people, I must admit, think that may have already happened). It's hard to imagine what an elderly person must be going through if they're no longer able to read or engage in physically demanding activity, especially if they were previously accustomed to social interaction.

The idea that social isolation could literally kill you is hard to explain. One possibility is that a person's psychological identity depends on interaction with others. These studies don't necessarily mean that a lack of stimulation is responsible, and some have metholological problems. For example, self-reporting of emotional states is unreliable. Many other factors could explain the correlation, including stress, age, dietary or hormonal changes, or even loss of bacterial diversity. But whatever the explanation, if the results are true it adds to a growing body of work affirming that human companionship is important for our health.

1. Torres JM, Sofrygin O, Rudolph KE, Haan MN, Wong R, Glymour MM (2020). Adult child US migration Status and cognitive decline among older parents who remain in Mexico. Am J Epidemiology. kwz277, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwz277 Link (paywalled)

2. Sundström A, Adolfsson A, Nordin M, Adolfsson R. (2019). Loneliness increases the risk of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. Oct 24. pii: gbz139. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz139.

3. Peterman JL, White JD, Calcagno A, Hagen C, Quiring M, Paulhus K, Gurney T, Eimerbrink MJ, Curtis M, Boehm GW, Chumley MJ. (2020). Prolonged isolation stress accelerates the onset of Alzheimer's disease-related pathology in 5xFAD mice despite running wheels and environmental enrichment. Behav Brain Res. 379, 112366. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112366. PMID:31743728

4. Bero AW, Yan P, Roh JH, Cirrito JR, Stewart FR, Raichle ME, Lee JM, Holtzman DM (2011). Neuronal activity regulates the regional vulnerability to amyloid-beta deposition. Nat Neurosci. 14(6):750–756. doi: 10.1038/nn.2801. PMID: 21532579

5. Filser S, Ovsepian SV, Masana M, Blazquez-Llorca L, Brandt Elvang A, Volbracht C, Müller MB, Jung CK, Herms J. (2015). Pharmacological inhibition of BACE1 impairs synaptic plasticity and cognitive functions. Biol Psychiatry 77, 729–739. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.10.013. PMID: 25599931

6. Fornari S, Schäfer A, Jucker M, Goriely A, Kuhl E. (2019) Prion-like spreading of Alzheimer's disease within the brain's connectome. J. R. Soc. Interface 16: 20190356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2019.0356

jan 18 2020, 4:12 am. edited jan 19 2020, 5:17 pm