oison ivy isn't just an annoyance: people have died from inhaling smoke from

burning the plants. The toxin is readily spread by contact with animals

or inaminate objects. One person of my acquaintance somehow got poison ivy

over her entire body. Though she wouldn't say how that happened, one

possibility is that it was caused by sunbathing, perhaps by lying on a

towel that had contacted it. In this article, I'll discuss how to recognize

poison ivy and explain why it causes such strong cases of contact dermatitis.

oison ivy isn't just an annoyance: people have died from inhaling smoke from

burning the plants. The toxin is readily spread by contact with animals

or inaminate objects. One person of my acquaintance somehow got poison ivy

over her entire body. Though she wouldn't say how that happened, one

possibility is that it was caused by sunbathing, perhaps by lying on a

towel that had contacted it. In this article, I'll discuss how to recognize

poison ivy and explain why it causes such strong cases of contact dermatitis.

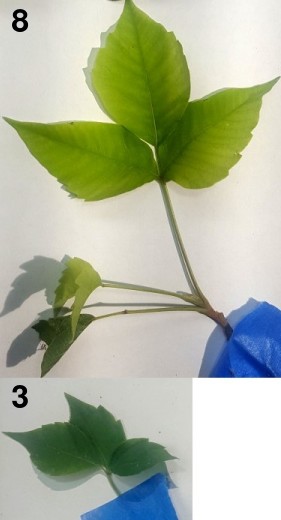

Poison ivy can be identified by its leaf shape (Fig. 1) and by simple tests. There are two types: eastern poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), which typically appears as a woody vine, and western poison ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii), which is a shrub and does not climb. Both species can occur together in overlapping parts of the USA.

Fig. 1. Poison ivy leaves. Sample #8 is from a standing poison ivy bush found growing next to a community swimming pool. Sample #3 is from a small trailing poison ivy vine found clinging to an oak tree. Notice the difference in color: poison ivy leaves need not be dark green and are not shiny

Leaf shape

- Three-leaf pinnate pattern with the center having the longest stalk. The three leaves all join at the same point.

- Toothed or lobed edge. Small leaves may only have one or two serrations, making them look bi-lobed like sassafras leaves. Leaves with sawtooth serrations or with smooth edges are not poison ivy.

- Leaf veins don't line up (may be 6 veins on the left, 5 on the right).

- Pointed tip, ‘almond’ shaped leaf.

- White drupes (sometimes called berries) may be present.

- No consistency of color; may be pale yellow-green or dark green, but not as shiny as ivy or laurel leaves.

- No thorns. The leaves resemble briar leaves, but anything with a thorn is not poison ivy.

- Poison ivy can can be trailing vines, standing bushes, or climbing vines. They may climb up the sides of trees or buildings. Some regions have more climbing forms and others have exclusively standing bushes.

- Climbing vines have reddish-brown hairy aerial roots that resemble fur. However, this type of root is not unique to poison ivy.

There are many scientific articles describing how to distinguish poison ivy from other plants. Unfortunately, I have never found one that is not behind a paywall. Most popular websites are useless, as it's hard to confuse virginia creeper, sumac, or strawberry plants with poison ivy. But even authentic poison ivy plants are not always the same. The best way to identify it is to use the paper test. (The second best way is to find a volunteer, preferably one you hate!)

Paper test

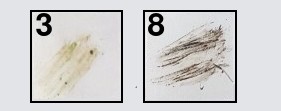

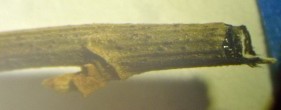

A classic test for identifying poison ivy is to cut a stem and rub the sap on a piece of white paper while wearing rubber gloves. If the sample is poison ivy, it will start to turn black after one hour. By twenty-four hours, it will be dark brownish-black (Fig. 2). Most other weeds show a negative result (Fig. 4). By 24 hours, the area on the stem near the cut will also turn black (Fig. 5). The black color is caused by oxidation of urushiol, the agent that causes contact dermatitis.

Fig. 2. Paper test for the two poison ivy specimens in Fig. 1. The black boxes were one inch square. Most weeds leave a green or colorless stain which fades over time, but poison ivy creates a distinctive brown-black mark after 24 hours. The small vine (Sample #3) had much less toxin than the mature bush (Sample #8)

Different plants have widely varying levels of urushiol. Wear rubber gloves while handling samples of poison ivy and clean all implements with acetone or denatured ethanol. If you wash the urushiol off your skin with soap and water or denatured alcohol within thirty minutes, you can avoid the immune reaction. However, some recommend washing with water only, in the belief that removing protective skin oils facilitates absorption.

Some other lab tests are more sensitive. For instance, one lab proposed a test that involves reacting it with a B-n-butylborinic acid, then reacting it with a nitroxide to create a fluorescent molecule.

Chemistry

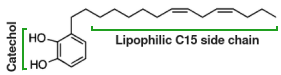

Fig. 3. Chemical structure of the most common urushiol in poison ivy

Urushiol isn't just one molecule, but a family of alkyl- and alkenyl-catechols that differ in the number of double bonds and the length of the lipophilic side chain. Toxicity increases with the number of double bonds. Poison oak contains a similar urushiol with a C17 side chain. A key feature of urushiol is its catechol group (Fig. 3). When urushiol is oxidized, the hydrogens on the two hydroxyl groups are removed and ring structure becomes a quinone. The quinone form covalently binds to proteins inside the cell. This is why oxidation of urushiol is necessary for it to be effective. It is also why washing it off within a half hour is often effective in preventing contact dermatitis. The oxidation happens spontaneously in air, so hypothetically it might be possible to prevent the dermatitis with antioxidants. However, the best way to prevent it is to wash it off before it can get absorbed.

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac are members of same genus Toxicodendron and produce urushiols. Metopium (poisonwood), found in the Florida Keys and West Indes, and Lithraea caustica (litre tree), found in Chile, are plants in the same family (Anacardiaceae) that are even more potent than poison ivy.

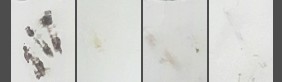

Fig. 4. Poison ivy and three negative tests of other weeds including briars and creeping ivy

Immunology

The most interesting thing about poison ivy is its effect on the immune system. Poison ivy causes contact dermatitis, as do ragweed, cashew shells, pistachios, mango peels, poison oak, and poison sumac, because the urushiols they contain are potent immune sensitizers. Thus, exposure to one species of the Anacardiaceae family will sensitize you to the others. Many other chemicals, such as latex, antibiotics, epoxy resin and hardener, and even nickel, are also immune sensitizers, but few are as potent as urushiol.

Fig. 5. Poison ivy stems turn black after 24 hours when exposed to air. This specimen had large amounts of urushiol, which causes the black color when it oxidizes

People tend to think it's a simple allergic response. But in fact the adaptive immune system, which makes antibodies and killer T cells, is involved. The clue is that poison ivy has a sensitization phase, which takes 6 to 10 days for strong sensitizers like poison ivy (and longer for weak sensitizers like nickel). In this phase, urushiol oil travels through the skin and into your skin cells, where it acts as a hapten by attaching covalently to intracellular proteins, making them antigenic. These proteins are then broken down in the cell by normal proteasomal activity and delivered, with the sensitizing agent still attached, to the cell surface as protein fragments (peptides) by specialized proteins called MHC class 1 histocompatibility proteins.

At this point, the immune system is able to sense that something bad is going on inside your cells. The Langerhans cells in the dendritic epidermis and dendritic cells in the dermis migrate to your lymph nodes, where they present the peptide (with the sensitizing agent still attached to it) to TH1 cells (helper T cells). This activates the T cells so they secrete interferon-gamma and other cytokines such as CXCL8, CXCL11, and CLXL8. From this, we get memory T cells localizing in the skin.

On the second exposure, CD-8+ T cells (known as “killer” or cytotoxic T cells) now recognize urushiol oil and kill any cell that contains it either directly or by secreting cytokines such as interferon-γ and interleukin 17.

Giant hogweed

The toxin in poison ivy differs from that in giant hogweed, which contains linear furanocoumarins such as psoralen, bergapten, and xanthotoxin. Unlike urushiols, furanocoumarins are not immunosensitizers, but are directly toxic, so a single contact exposure can cause severe phytophotodermatitis. These molecules structurally resemble nucleotide bases. Longwave ultraviolet light (320–380 nm) catalyzes adduct formation of the furanocoumarins with DNA and RNA. Photoactivation also causes formation of covalent adducts with fatty acids, causing cell membrane damage and edema leading to cell death. Besides giant hogweed, figs, citrus fruits such as limes, and members of the carrot family such as parsley and celery, also cause phytophotodermatitis, but are less potent.[1]

This may all sound very complicated, but poison ivy is one of those phenomena that have taught us how the immune system works. For reasons that are not clear, humans are almost the only species affected by poison ivy. Nonmammalian species such as molluscs and insects lack an adaptive immune system and have no problem eating poison ivy. And as far as I'm concerned, they're welcome to eat as much of it as they want.

[1] Burrows GE, Tyrl RJ. (2001). Apiacae Lindl., Toxic Plants of North America, Iowa State Press, p.45

aug 18 2023, 3:56 am