apers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time. So say

three people from the Carlson School of Management in Minnesota and

the School of Sociology at Arizona[1].

apers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time. So say

three people from the Carlson School of Management in Minnesota and

the School of Sociology at Arizona[1].

Every once in a while a paper comes along telling us what everybody already believes. Ask any scientist whether we're making fewer major discoveries and they'll probably agree. Then they'll start ranting about being forced to spend all their time writing papers and grants.

Test tube rotator from a typical academic lab

Then they'll rant about how academics are forced to work with out-of-date equipment. In my case, for instance, the most advanced stuff I have is equipment I built at home. Without that, I'd be unable to do any work at all. What equipment the university provides is held together by duct tape. On some of it the label “Made In West Germany” has almost worn off. It's not just here. In every academic lab I've been in, something needed board-level repair before it would work.

Or they'd rant about the fact that our bureaucrats cancel grants that somebody spent months writing just to get revenge on somebody's co-investigator. It doesn't matter to them: they get paid by the state. Or they could rant about the hiring process, where applicants who don't write a convincing enough diversity statement, where they must prove their demonstrated commitment to the popular ideology on campus, are automatically excluded, thereby ensuring groupthink, lack of intellectual diversity, and politicization in science.

But that's not what this paper says. It creates a new metric called a CD index that supposedly characterizes how papers and patents change “networks of citations in science and technology.” They write

The lack of innovation poses substantial threats to . . . efforts to combat grand challenges such as climate change.

Am I the only one who thinks that pursuing popular scientific fads like climate change is another reason no one is making progress? We're all bogged down in fads because we depend on the government for funding, and the government loves fads.

The CD index works this way:

If a paper or patent is consolidating, subsequent work that cites it is more likely to cite its predecessors. . . . We measure the CD index five years after the year of each paper's publication.

They also say

The CD index has been validated extensively in previous research, including through correlation with expert assessments. . . .

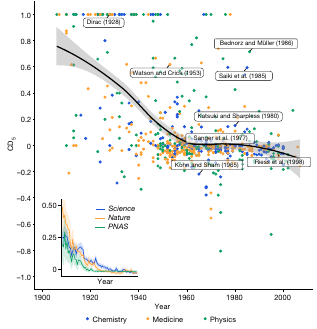

[W]hen we restrict our samples to articles published in premier publication venues such as Nature, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and Science or to Nobel-winning discoveries (Fig. 5), the downward trend persists.

Those all-knowing “experts” at work again. But there's a bigger problem: their analysis is fatally flawed. Most of the graphs are typical line graphs showing that their Index decreases, apparently dramatically, over time. But take a look at Fig. 5 in the paper, which shows their extended data in more detail. The figure shows a line of data points at the top left and a bunch of scattered data points in the rest of the graph. This is evidence of two populations, not a decline. If so, all their correlations and graphs are analyzed incorrectly.

Graph of disruptive science vs time (Fig. 5 from Park et al.). There are clearly two clusters here. The cluster along the top is the only reason the trend is statistically significant

We see data sets like this all the time. An example is in qPCR genotyping, which gives us a plot much like this. No one would draw a correlation curve on such a graph. You must do an unsupervised cluster analysis. The authors' graph is screaming at us that there are two populations and demands an explanation. Without those data points at the top, the correlation would be a horizontal line.

The authors failed to prove their case. That's quite an accomplishment considering that it's something everyone already knows. But maybe we should re-evaluate that. That would have been a disruptive result.

In short, their CD index is just a new form of citation analysis and it won't solve the problem. In fact, citation analysis is arguably what got us into this mess and CD index would must make things worse.

Of course, if they had done their analysis correctly they wouldn't have gotten a simple snazzy result that confirms what everyone already believes, and just coincidentally flatters the editors of Nature, and they wouldn't have gotten published there. Getting into a “top” journal, not making breakthrough discoveries, is now the goal of science. Productivity, or disruptiveness if you will, has not really declined; it is the goal of science that has changed. If those in power wanted disruptive science, they'd measure success by disruptiveness. If they wanted cures for diseases, they'd measure success by cures. Instead they use simple, easy-to-calculate indices like citation analysis, publication counting, and now CD analysis. And so what they get is people writing lots and lots of papers.

What makes this so remarkable is that these economists forgot the first rule of economics: you get what you pay for.

[1] Park M, Leahey E, Funk RJ. Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time. Nature. 2023 Jan;613(7942):138-144. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05543-x. PMID: 36600070.

jan 06 2023, 6:23 am