verything is a crisis these days. It's not enough to have a heat wave.

No, it has to be the biggest heat wave ever in the history of planet Earth.

Science can't just have some researchers who need more training about

how to do experiments. No, it has to be a reproducibility crisis. And

of course, we just by the skin of our teeth managed to survive that last

crisis, whatever it was, some virus I guess.

verything is a crisis these days. It's not enough to have a heat wave.

No, it has to be the biggest heat wave ever in the history of planet Earth.

Science can't just have some researchers who need more training about

how to do experiments. No, it has to be a reproducibility crisis. And

of course, we just by the skin of our teeth managed to survive that last

crisis, whatever it was, some virus I guess.

The crisis mentality leads, by analogy to Newton's First Law, to an equal and opposite mentality of crisis deniers. As one side becomes more extreme, the other follows in the opposite direction. This turns an ordinary everyday crisis into a moral crusade for the survival of mankind, feeding an expanding cycle of exaggeration.

In my new unofficial role as a scientific imaging consultant, I've been trying to teach people basic stuff about data presentation that they should have learned in graduate school. Last week one lab forwarded me a weird letter they received from a journal about their recent paper. It turned out that one of the PI's enemies, a high-ranking professor at their school, had sent the journal an anonymous letter accusing them of faking their images. This wasn't the first time this happened there: that school is a veritable Peyton Place where everybody hates everybody else. You can tell that's the case because it's academia. In academia if someone smiles at you, it means they hate your guts. Also, if they don't smile at you, it also means they hate your guts.

What was wrong with this guy's paper? The journal invented a bunch of claims that made no sense and were easy enough for me to refute. But the fundamental problem was the way they presented their data. They were convinced that a Western blot had to be as dark as possible, so they made them so dark it looked like someone had taken a Magic Marker and drawn them in by hand.

They were not happy when I told them that this meant all their densitometry results were invalid: there was no information left in the image, which was why all their numbers were the same. Ironically, the original images were so light that the bands could hardly be seen. Long story short, they eventually fixed it.

(And where oh where was their new lab director the bureaucrats appointed to catch things like this? Three letters: MIA.)

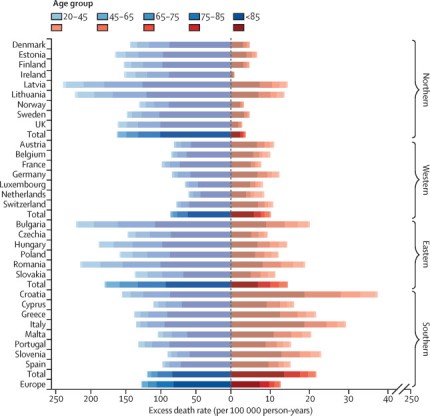

Another case turned up in Lancet last week in a paper on global warming. The paper was telling us something we already knew: that cold weather kills more people than hot weather. They plotted the excess death rates from the 1% coldest and 1% hottest temperatures (which they call the 99th and the first percentile) for various countries. Here's the graph, reduced in size to fit this page:

Misleading global warming data graph from Lancet

Notice what they've done. The scale for the hot temperatures is one-fifth

that of the cold temperatures, which makes the hot and cold deaths look

almost the same. They are not. Their own results show that cold weather

kills 10.09× more people than hot weather. The effect was higher

in eastern Europe, where the median age is higher and cities are more

distant from the moderating effects of the Atlantic. The effect was true

in hotter countries like Spain (6.45×) and Greece (6.34×),

though as expected a higher ratio occurred in colder countries like

Sweden (30.75×) and, for some reason, Ireland (158.9×).

These two examples of scientific exaggeration might seem unrelated. But the question is: are they scientific fraud? It boils down to whether they're trying to deceive you. In each case, the authors biased the data presentation toward the conclusion they wanted people to see. The Lancet authors know that their audience are desperate for data that would show AGW kills people and would interpret the graph as such (for why else would anyone read The Lancet but to learn about global warming?). It may also be relevant to ask whether Lancet would ever publish an article that would support what global warming skeptics are saying. Likewise, the lab that made those Western blots was very anxious that if their bands were not dark enough their paper might not be accepted in a good journal.

There are hundreds, if not thousands, of similar examples in the scientific literature. When scientists misinterpret their own data, even if all they do is present accurate data dishonestly, they can lead researchers on a wild goose chase that can prevent diseases from being cured. Or they can lead politicians and bureaucrats to invent more rules to fix a non-existent problem.

I conclude that these are all examples of crisis inflation, where journals and peer-reviewers judge papers on the basis of their potential impact, which is a polite way of saying whether they conform to their pre-established prejudices. A paper is, after all, merely an advertisement for the authors' hypothesis, but unlike commercial advertisements where money is involved, the only factor that ensures honesty in science is personal integrity.

Scientific journals are the gatekeepers in science and they are largely responsible for this bias. This was shown conclusively during the Covid crisis, when hundreds of papers on clinical drug trials were published not because of their scientific merit but because of their newsworthiness in the crisis. The overall effect was to seriously damage the credibility of clinical science, and even more so of the big science establishments (NIH, CDC, and FDA), whose pronouncements used to be taken as gospel.

Likewise with the press and their crises, the latest of which is about someone named Victoria Beckham wearing yellow Crocs boots. The crisis atmosphere is intensified by those speeded-up videos purporting to show people fighting furiously with each other. The net result is that people, especially young people, now get their news from social media and regard newspapers as mere entertainment.

Does this mean we have a crisis inflation crisis? Or is it a crisis crisis? People are notorious for being able to focus only on one crisis at a time. We could even say too many crisis crises lead to a crisis crisis crisis. But we would never say such a thing here, because we're too responsible.

jul 26 2023, 8:26 am