e can deny it or ignore it, but science is under attack. Thanks to science's

fraternization with global warming advocates, many people have come to see science

as a political movement. On the left there are increasing numbers, like Sara Giordano,

who claim to

think

that the epistemic authority of science comes from colonialization, racism, and slavery.

And there are still a few religious people criticizing us for the theory of evolution,

like Japanese soldiers fighting in the jungle after the end of World War II.

e can deny it or ignore it, but science is under attack. Thanks to science's

fraternization with global warming advocates, many people have come to see science

as a political movement. On the left there are increasing numbers, like Sara Giordano,

who claim to

think

that the epistemic authority of science comes from colonialization, racism, and slavery.

And there are still a few religious people criticizing us for the theory of evolution,

like Japanese soldiers fighting in the jungle after the end of World War II.

If there is any truth to claims about a reproducibility crisis, much of the blame has to fall on the working conditions in academia, where scientific careers rise or fall based on the judgment of bureaucrats whose only knowledge is of citation indexes and impact factors, and their ability to count the number of papers per year.

But some of it has to do with our dependence on industry. Over the past fifty years, scientists have become utterly dependent on our biotech infrastructure: the maze of small companies that supply antibodies and reagents to research.

It wasn't always so: when I first started out, it was normal to start out by purifying whatever enzymes you needed for your research. This was a tedious process that sometimes meant a trip out to the slaughterhouse (ours was at Mount Airy, Maryland), and always involved low-pressure columns and spending hours watching fractions dripping one by one into an automated fraction collector.

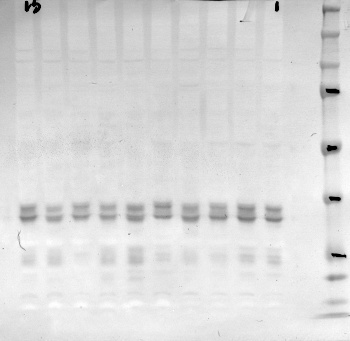

A Western blot showing two forms of a protein called ApoE. But how sure are we about that?

Nowadays, of course, we buy them from companies instead. It's much faster. and instead of setting up assays, we use kits. (I blame the DNA guys for that. They started with the kits.)

But yesterday something happened in my lab that made me realize just how dangerous that dependency has become. A colleague had purchased an antibody from one such company and began studying one signaling protein (I won't disclose the name, lest he get scooped; anyway, it's just a meaningless series of letters.) He performed a procedure called immunoprecipitation to get a sample of the protein for study. I offered to analyze it for him using mass spectrometry, a large and very expensive instrument that tells you unequivocally what proteins are in your sample.

I found that the protein he'd isolated was vimentin, which was identical in all respects to the real protein—its molecular weight, its tissue distribution—except that it was the wrong thing. Vimentin is what we call a sticky protein, which means it attaches to other proteins, like antibodies, a lot.

Maybe the average person won't understand how scary this is. It might not be up there with being buried alive or listening to David Hasselhoff trying to sing, but it's close.

How often do academic researchers test their reagents this rigorously?. If they did, how many of them would turn out to be contaminated, or as in our case, completely wrong? If we had to test everything, we'd soon find ourselves working as used car salesmen, elephant cage cleaners, or—gasp—pharma sales reps.

In most cases, I suspect the researcher—and it's mostly grad students and postdocs these days, who are working against the clock—will just say the experiment didn't work and toss everything into the trash. Can we believe the CoAs (Certificates of Analysis) that come with these products? Should basic researchers analyze every chemical we buy to verify its purity and authenticity, as the FDA requires pharmaceutical companies to do when manufacturing a drug?

This is part of GLP, or Good Laboratory Practice, and GLP is a nightmare. Only companies that do things that directly affect human health use it, because it multiplies the cost by a factor of ten. Does the taxpayer really want to pay for that?

Often we don't even know what's in those kits: the only way to find out is to look up the patent. Our experience shows that for antibodies, a Western blot is not enough. You must spend a week doing an IP and LCMS. This is what we plan to do from now on.

All this guy's experiments, probably two months of work, have to be thrown out because some corporation sold us an antibody that cross-reacts with another protein of exactly the same molecular weight, and then denied that it could be happening. And that's why i get so exercised when somebody in industry accuses academics of doing irreproducible research.

It's not the first time this has happened. Just one example: we have a $60,000 spectrometer sitting idle because some corporation out in California sold us a xenon lamp power supply that crapped out after one hour of use. We RMA'd it and they finally replaced it with a new one—eight months later.

Sure, stuff breaks, it happens. But I wonder whether the people criticizing science really want us to stop searching for cures for their diseases and go back to the old days when we built all our own equipment, synthesized all our reagents, and blew all our own glassware. It so happens I like building equipment. But it won't save many lives.

oct 26, 2017, 5:00 am