t's become fashionable to complain about a “reproducibility crisis” in

science. Some of it, I suspect, is a form of boasting: everyone else's research is

irreproducible, they're saying, but their own. There is a huge problem in science,

but it's not reproducibility, it's superficiality.

t's become fashionable to complain about a “reproducibility crisis” in

science. Some of it, I suspect, is a form of boasting: everyone else's research is

irreproducible, they're saying, but their own. There is a huge problem in science,

but it's not reproducibility, it's superficiality.

This might sound surprising, or even heretical in an age where superficiality is considered a virtue, but it creates challenges (we're not allowed to call anything a ‘problem’ these days, lest we be accused of being negative). But consider: the US National Library of Medicine lists a total of 3,932,518 articles on cancer, 1,368,261 articles on heart disease, 151,978 on Alzheimer's, and 119,594 on Parkinson's disease.* If a cancer researcher read ten papers per day, it would take 1,077.4 years to get caught up, assuming no new ones came out over the next millennium. Since no one can possibly do this, they can unknowingly repeat previous work, and it snowballs.

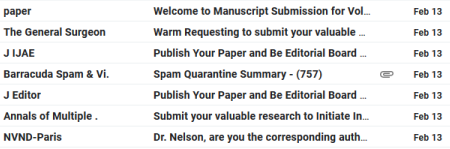

The demand for places to publish all this stuff has created an entire industry, and a new type of spam to go with it. Below is a screenshot of my spam folder for one day, on one computer. Except the one from Barracuda, all are from journals asking for articles. The Barracuda one is from an old system I set up back in 2000. Despite the fact that the organization that ran it has long since gone bankrupt, it is still running and still filling up with spam and still dutifully forwarding a list of spams to me. There are a bunch more requests for articles in that list of 757 spams from February.

Spam folder screenshot

Of course, a few are just traditional spam, like the ones claiming to have recorded salacious videos of me. These, I must admit, are impressive considering that none of my computers has a camera. For a mere $2000 in bitcoin, they say, they will refrain from sending the compromising videos to my friends. Little do they know I'm rapidly approaching the age where I'd pay them $2000 to send those videos to my friends. My friends would be impressed.

It's nice to be wanted, if not to be surreptitiously recorded, but it's a symptom of a problem . . . er, challenge. Scientists are under enormous pressure to write as many papers as possible, and to get them in top journals, and as with Internet opinion articles (not, of course, including this one), the balance shifts from quality to quantity.

Last month a colleague sent me a bunch of his reprints, all of which were in good journals. There was no question that his findings were reproducible. And there was also no question that they were all describing the same phenomenon.

He'd gotten ahold of some peptide that he's hoping will be a treatment for some disease. The peptide did stuff to the mice, making them a bit healthier. It reduced the levels of this bad molecule, and it improved the numbers on that other good molecule. Okay, okay, I was thinking, I get it. So do a frickin' clinical trial already. Better yet, do a frickin' Koch experiment.

If you ever wondered why biomedicine is stagnating, here's the reason: people seem to have forgotten Koch's Postulates. These postulates don't just apply to proving trigger factors like cholesterol; they're needed to establish the molecular mechanism of a treatment as well.

I'm being purposely vague about that peptide researcher because he is a good scientist, but when career survival demands five or ten papers a year, it forces even good scientists to publish shallow articles. They may or may not reproducible. We'll never know, because so few people read them. Most of them are not worth reading. Many of the findings are not even worth writing down.

Those scientists who invented MRI went for years without publishing. Then they finally got it to work, and it revolutionized medicine. That can only happen in an environment that encourages deep science. If you tried that in academia, you'd quickly become unemployed and unemployable.

Nature, a global-warming-womens-rights magazine that occasionally also publishes science-related articles, has an opinion piece this week by a guy named Alan Finkel. Finkel starts out saying that training and mentorship should be mandated, and supervisors should be required to train equal numbers of male and female students. Finally he gets to his main point: there are too many frickin' papers! (I'm paraphrasing). He suggests the rule of five, where candidates present only their five best papers. This, he says, would beef up quality.

He's mainly concerned with reproducibility. But if bureaucrats would stop telling scientists how to do their jobs, reproducibility would follow as night follows day, or as commercials follow How the Universe Works (which, at the risk of sounding negative again, is about the only show on television I can stand to watch). Bad science comes from a reward system that is based on the only thing bureaucrats know how to do: count. Society gives them control over the funding, and the reward system they created is damaging the reputation of science.

There's a lot of concern these days about fake news. When the number of fake news stories equals the number of true stories, we will get no net truth from the media. Viewers who watch the news will be less well informed than those who don't.

Science isn't close to that yet, but we're moving in the same direction. My solution is simple: no one should be permitted to publish more than two papers per year. That would mean only the stuff that's really solid and really exciting ever gets published.

Scientists are people too, and they must provide what those in power demand. Therefore, as power-hungry bureaucrats gradually mutate into dictators, the purpose of science changes into a way of supporting the bureaucracy. Finding cures has become incidental: all that matters is getting more grants and papers so the bureaucrats can count them. People in academia seem to be cool with this, or perhaps they are too intimidated to speak up; and the ones who ought to care, which is to say those whose loved ones are dying of horrible diseases, wonder why, after all these years, no one appears to have found a cure.

Sociologists think scientific productivity is declining, but it's not; it's just that the definition of productivity has changed. All systems eventually become nothing more than ways of propagating the system. By that metric, we're more successful than ever.

* Search terms: cancer = cancer or carcinog*; heart disease = heart disease or atherosclero*; Alzheimer's = alzheimer*; Parkinson's = parkinson's disease or parkinson*[tw]).

feb 23 2019, 5:51 am. last edited feb 24 2019, 5:07 am