Book Review

f you like Russian novels because there are so many characters, with strange

names that all sound pretty much alike, then you'll love J.R.R. Tolkien's

The Silmarillion, where there are hundreds of them, with names

like Finarfin, Finduilas, Fingolfin, Finwë, Fingon, and Finrod (just

to name a few). The Index of Names in the back takes up 51 pages, and many

characters have several different names. Each plays a role in a vast story

that spans the rise and fall of an entire civilization

over a period of nearly 5,000 years.

f you like Russian novels because there are so many characters, with strange

names that all sound pretty much alike, then you'll love J.R.R. Tolkien's

The Silmarillion, where there are hundreds of them, with names

like Finarfin, Finduilas, Fingolfin, Finwë, Fingon, and Finrod (just

to name a few). The Index of Names in the back takes up 51 pages, and many

characters have several different names. Each plays a role in a vast story

that spans the rise and fall of an entire civilization

over a period of nearly 5,000 years.

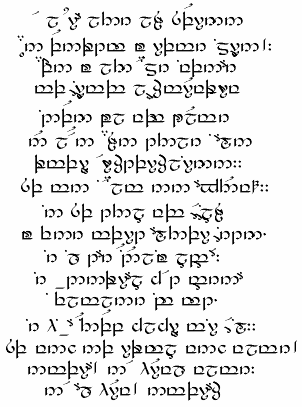

Example of Tolkien's Quenya (Elvish) language in Tengwar script. (Credit: This image was created from a plain TeX demo file for Mike Urban's Tengwar font, which is available on CTAN.)

The largest section of the book is called Quenta Silmarillion, which means History of the Silmarils, which are luminous gems created by Fëanor, the eldest son of Finwë, half-brother of Fingolfin and Finarfin. Finwë is the elf who led the Noldor on their ill-fated journey from Cuiviénen, which set in motion the ultimate downfall of the Elvish kingdoms in the First Age.

Now, if you're a Tolkien fan, you probably know all this already, so this is boring. If not, you probably have no idea what I'm talking about. So let me start again.

The Silmarillion is the back-story for Lord of the Rings. It's written in an archaic, almost King James style English. It has its own creation myth, deities and sub-deities, but unlike the Bible, it's pure fantasy: there are no Ten Commandments, no Psalms, and no admonitions about what kinds of food you're not allowed to eat, just the history and genealogy of the Elves, Dwarves and Men (who come late to the party). There is strong inspiration from Celtic culture and Nordic mythology, and even hints of Slavic (the Elvish city of Nogrod being one example). Tolkien's fantasy world is colorfully described, with sentences like “Then through the Calacirya, the Pass of Light, the radiance of the Blessed Realm streamed forth, kindling the dark waves to silver and gold, and it touched the Lonely Isle, and its western shore grew green and fair.”

Yes, the prose is fanciful and somewhat purple, but you get used to it. In the story Ilúvatar, the creator, neglects to create the Sun or Moon. Two trees actually emitted light of their own, providing sufficient illumination, which was lucky since the bad guy Melkor (aka Morgoth) destroyed the only two lamps on this strange world. It was not until Morgoth destroyed the two trees as well that the Valar take up the task of creating the Sun. (They mucked it up, and the Sun rose in the west at first, but by page 243 that little glitch has been fixed).

Or maybe I missed something. You have to pay close attention to all these characters. At one point after a brief conversation, a lady named Ungoliant enmeshes Morgoth (aka Melkor) in a web of clinging thongs. (Luckily for him, he was later saved by some Balrogs.) It was all very confusing, but after paging back a few pages I realized I had missed the fact that Ungoliant is not actually a lady, but a Typical sentence “Few of the Eldar went ever to Nogrod and Belegost, save Eöl of Nan Elmoth and Maeglin his son; but the Dwarves trafficked into Beleriand, and they made a great road that passed under the shoulders of Mount Dolmed and followed the course of the river Ascar, crossing Gelion at Sarn Athrad, the Ford of Stones, where battle after befell.” [p. 101] giant talking spider (try explaining that to your wife).

The deity Ilúvatar created everything in much the same way as the biblical God: by thinking and speaking it into existence. But it's not really explained how Aulë, who is a Vala, one of the great Ainur, or Holy Ones, who entered into Eä (the material universe) at the beginning of time, created the Dwarves. Was he a genetic engineer? Did I mention that this story is very complicated?

So, yes, the molecular biology is vague and the physics is nonexistent, but it's an incredibly rich fantasy world, full of geopolitics and conflict and the rise and fall of civilizations (which is attributed to the Silmarils and to the rise of the machines), and underneath it all, a longing for a glorious age of beauty and magic long past. Tolkien had a deep understanding of the large sweep of history and the role of courage, weakness, betrayal, and woefully inadequate battlefield strategy in causing tragedies on a civilizational scale.

You will also learn the origin of the Balrogs and Sauron, possessor of the all-seeing flaming Vagazzle, as it's depicted in the movie, and what it means when the Elves say they are “going West.” Most of all, you will learn what it feels like to watch helplessly as your civilization faces destruction. I won't give away the ending, but it's safe to assume that not everyone lives happily ever after in this monumental fairy tale.

If you're considering reading Tolkien's fiction, I would not recommend starting with Silmarillion. It will only give you a migraine. Read it after watching the LotR movie or reading one of his other books. The stuff here gives background and depth to Tolkien's other works, including The Tale of the Children of Húrin, and it's what gives The Lord of the Rings its epic magnificence.

Frankly, I would have liked to have seen more about Tolkien's imaginary languages: Quenya and Sindarin, and the beautiful scripts they're written in. He didn't write this book in Sindarin. But I'd be surprised if he hadn't considered it.