|

book reviews

More books by maverick scientistsreviewed by T. Nelson |

|

book reviews

More books by maverick scientistsreviewed by T. Nelson |

by Karl Herrup

MIT Press 2021, 257 pages

Reviewed by T. Nelson

By now, most people know what happens to scientists who challenge the prevailing dogma: they are ignored and ridiculed, their funding dries up, and eventually they're driven out of science. Decades later they're proven right. They get a Nobel Prize (if they're still alive), our scientific leaders congratulate themselves on the success of the scientific method, and a new unchallengeable dogma is born.

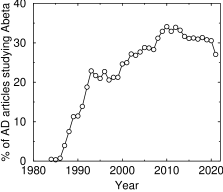

Percentage of AD articles studying beta-amyloid. This only includes papers with ‘beta-amyloid’ in the title or abstract

For almost forty years, the unchallengeable dogma in Alzheimer's disease, or AD, has been that it's caused by a build-up of a small protein called beta-amyloid, which forms amyloid plaques in the brain. Even today, AD is classified as a “protein folding disorder.” Despite the fact that over 600 clinical trials of anti-AD drugs have failed—including aducanumab, an antibody against beta-amyloid that the FDA recently approved—the percentage of AD papers studying beta-amyloid has scarcely changed (see graph).

If the general public knew about this, they'd be outside the doors of our labs with pitchforks.

This popular-style book explains how science got into this mess. It's easily understandable by a layman with no background in science, but it's also important for scientists to read it. It's especially important for my friends and colleagues at the NIH's Center for Scientific Review, because these days NIH funding is the main determinant of what we can study.

Karl Herrup is one of many who have argued against the beta-amyloid theory. But what to replace it with? One possibility is inflammation. Herrup's theory is that unrepaired DNA damage causes the inflammation in AD, and that inflammation, not beta-amyloid, is what kills our neurons. A corollary is that beta-amyloid does not cause inflammation but is actually induced by it as a defense. But good luck getting any of that published, let alone funded. Even Herrup had to be careful in his Journal of Neuroscience article not to mention AD until the end. The dogma is, as Herrup was told, “If you're not studying beta-amyloid, you're not studying Alzheimer's disease.” Every risk factor has to be hammered into the beta-amyloid paradigm. The cholesterol-carrying protein apolipoprotein E, for instance, works by mediating “clearance” of beta-amyloid. TREM2, a protein in microglia that participates in inflammatory signaling, is only relevant because it's activated by beta-amyloid.

This focus on the “bad protein” theory requires us to ignore its limitations. Herrup says that defining AD as a disease of beta-amyloid, as industry and government have done, is circular logic. More than that, in my opinion, it turns it into a non-falsifiable hypothesis, or maybe an example of the One True Scotsman fallacy: if a patient doesn't have amyloid plaques, then by definition he's not a true AD patient, but something else. The data are telling us this definition no longer works. Many people have plaques but not AD; many more have AD, as determined by clinical testing, but few plaques. And we now know that getting rid of the plaques and the soluble beta-amyloid has no effect on the disease.

This is an enormous problem for researchers: if there is no objective way of determining whether a patient has the disease, there is no chance of curing it. No non-human animal, not even genetically engineered mice, ever gets AD, so until basic researchers discover what causes it, all that can be done is to run random clinical trials based on hunches.

Unfortunately, that's what the NIH is doing. NIH's response to the brick wall we've rammed into is to redirect funding away from basic research and toward more clinical trials—in other words, to repeat the same failed strategy that gave us 176,969 papers so far on the subject and almost nothing to show for it.

Herrup suggests reorganizing the funding agencies by moving AD from the National Institute of Aging to NINDS. NINDS bureaucrats would love that, but it's just rearranging the deck chairs. If we're going to cure things faster, fundamental changes will be needed in how we fund science.

oct 23 2021

by Geoffrey C. Kabat

Columbia, 2008, 250 pages

Reviewed by T. Nelson

Remember the hysteria about health risks from power lines, radon, and secondhand tobacco smoke? How about the deadly breast cancer epidemic? These were big deals only sixteen years ago. Nowadays, of course, we're far more sophisticated: we panic about gas stoves, red meat, “forever chemicals,” the weather, and tiny bits of plastic. And cows. Yes cows.

Geoffrey Kabat is a highly respected epidemiologist—don't laugh, they exist—who consulted with a fellow UCLA academic named James Enstrom to help him finish a study on secondhand smoke, also known as environmental tobacco smoke or ETS. You can read it yourself: it's a fine study.

In the 1970s, when smokers were common, the NEJM estimated that the average person's exposure to ETS was equivalent to 0.004 cigarettes per hour or 7 cigarettes per year. Today, of course, it's lower because fewer people smoke. Kabat believes smoking should be banned altogether, but also that we should be allowed to hear the evidence first. He writes:

It is entirely plausible that in some cases exposure to ETS may account for a few cases of lung cancer in nonsmokers, but . . . it is not possible to quantify the excess risk with certainty. [p.150]

A 25% increase in risk . . . is at the limit of what can reliably be sorted out in observational epidemiologic studies.[p.160]

That is about where ETS stands today. But there was a problem: Enstrom's funding ran out and the study was completed with funds from CIAR, a nonprofit group funded by tobacco companies. The anti-smoking activists viciously attacked and denounced the study and slandered the two authors, not because the study was flawed, but because of the funding source.

And they are still attacking it today: read the reviews of this book on Amazon for an example. It is, as Kabat says, McCarthyism in science. My opinion is that turning it into a moral crusade is a mask for ordinary everyday bigotry, but Kabat says the goal is not to evaluate the evidence but to ban ETS as a back door to banning smoking altogether, which they can't do because of public resistance.

The other chapters discuss radon, a naturally occurring form of radiation that terrified homeowners who realized their house might become unsalable and there would be nothing they could do about it. It turned out that the risk from radon was only measurable in miners exposed to huge quantities of it, and among smokers, who everybody hates anyway, so the problem was mostly forgotten. It's also support for the so-called two-hit theory, which says a cell only turns cancerous if two different biochemical pathways are disrupted.

Then there was the idea of an epidemic of breast cancer caused by pollution. The concern was so great in those days that there were giant buses driving around giving people free mammograms in an attempt to fight it. While breast cancer is still a major health problem, the idea of a sudden epidemic, according to Kabat, was a classic case of bad statistics. Women on Long Island had a 9–16% higher rate of breast cancer. A study came out claiming a strong association with DDE, a metabolite of DDT, but the actual data in the paper showed no such effect. No matter: few read or understood the paper. After a massive panic, the reason for the higher rate turned out to be that the women were older and had fewer children—known risk factors. Also, they were wealthier so they got screened more often. Despite massive press attention, 22 follow-up studies failed to reproduce the original claim. All because there was no sudden epidemic to begin with.

Another scandal was the idea that electromagnetic fields from power lines caused cancer. According to Kabat, an epidemiologist named David Savitz deliberately used ambiguous language after disproving that link in order to get more funding. This caused a media feeding frenzy and wasted hundreds of millions of dollars on studies that had no possibility of success. Instead of censuring Savitz, scientists (including Kabat himself) approved his approach because it got them a big increase in funding from DOE, NCI, NIEHS, and the electric power industry. But the evidence was never reproducible, in part because it would be physically impossible for radio waves to do it.

Kabat's story is a reminder that people don't want truth. They want a villain—a greedy industry or a paid-off researcher or a dangerous molecule—because it means there's a simple solution: get rid of the bad thing by bankrupting, cancelling, or banning it and every problem will be solved. They attack any scientific findings that challenge their simple beliefs. Kabat quotes Michael A. Gallo:

Toxicologists . . . have perpetuated the idea that if 100 molecules are going to kill you, then one molecule is going to kill 1 percent of somebody.

People really believed, based on this faulty logic, that secondhand smoke killed 40,000 people each year. Professionals in the field were afraid to dispute this claim for fear of being tarred and nicotined as industry stooges—and also because it meant more funding—so they remained silent. Activists will always crave power and scientists will always crave funding. So people will continue to invent stories, misrepresent their results, suppress facts, and slander anyone who gets in the way.

nov 01 2024. updated nov 08 2024