Celebrating our petrochemical culture

Our chemical industry may not be glamorous, but to the engineering mind its purpose makes it beautiful.

ive years before the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico a

catastrophic petrochemical explosion in Texas City, a small industrial town on

the Gulf coast, killed 15 workers and injured 180 others. It too was owned by BP,

formerly known as British Petroleum.

ive years before the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico a

catastrophic petrochemical explosion in Texas City, a small industrial town on

the Gulf coast, killed 15 workers and injured 180 others. It too was owned by BP,

formerly known as British Petroleum.

The accident occurred during restart of an isomerization unit, where the Penex process was used to catalytically[1] convert linear alkanes like n-pentane and n-hexane to branched hydrocarbons (e.g., isopentane and isohexane[2]), thereby giving them a higher octane value. One component was a 154,800-gallon distillation column (called a splitter tower) that separated the resulting raffinate (a mixture of high and low density aliphatic hydrocarbons) on the basis of their density.

On the afternoon of March 23, 2005, a defective alarm on the splitter tower led overworked operators to allow it to overfill. About 51,900 gallons of heated liquid hydrocarbons overflowed and were vented into a special tank called a blowdown drum at a rate of 509,500 gallons per hour. Unfortunately the drum and stack had a fill volume of only 22,800 gallons. Some of the excess was diverted, but the remainder sprayed out into the atmosphere and fell to the ground and formed a vapor cloud, causing a massive explosion.

The explosion caused US$ 1.5 billion in losses. The US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board report was damning in its criticism of BP's operations and safety culture, and the company eventually sold the Texas City plant to help pay for the Deepwater Horizon cleanup.

Texas City blowdown drum (arrow) and trailer wreckage (photo from CSB)

I lived in that area and visited Texas City many times. Whenever I visited it, day or night, the odor of chemicals was always in the air. Even in the summer, despite the 102 degree heat, I kept my windows in my non-air-conditioned Toyota Corolla rolled up whenever I got within two miles of the town. Afterwards I would take deep breaths of the sweet smell of the diesel fumes and exhaust of the cars stacked up on I-45 in the Houston traffic jams to clear my system of the isohexanes, isopentanes, 1,3-butadiene, and whatever else they were making.

The average person might not appreciate it, but to a chemist Texas City is a beautiful and fascinating place. To a chemist, Texas City is Disneyland. Huge white towers, standing like missiles ready for launch, stretch off into the distance, connected to each other with pristine white pipes. Giant cylindrical tanks of chemicals and hydrocarbon products are lined up in neat rows. Just as physicists to to Alamogordo on their vacations, we go to east Texas.

People love chemicals in these parts of America. Though they can be risky—the chemicals can be toxic, and a single mistake can have devastating consequences—when done carefully the technology is impressive and high-tech. Instead of high density polyethylene wheelie bins like they use in England, many Texas City residents store their trash in empty 55-gallon drums with markings of various chemicals in big letters. At night the cracking towers are lit up with dozens of lights, making this no-nonsense industrial town look more like a big city than a town of 40,000.

The locals never seemed to notice the smell. I always suspected they had evolved an immunity to it, like the Sherpas who are resistant to altitude sickness. But across the bay, when the wind blows in the wrong direction, the residents of Galveston get a reminder of where their gasoline comes from, and they complain.

A discussion of ghastly smells is not complete without mentioning Neville Island, a five-mile-long island in the Ohio River in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

This is the site of the Neville Chemical Company, a 90-year-old manufacturer of synthetic hydrocarbon resins and coumarone-indene resins. The plant is a maze of chemical storage tanks and rusty pipes that lead in all directions, so dense that in some places they nearly block the overhead view. Google's satellite view shows that the tangle of pipes and the pothole-filled road, which splashed what I hoped was only water when I drove through it, are visible from space. The water had a beautiful rainbow sheen from a fine molecular layer of hydrocarbons on its surface, and the rusty pipes and, I assume, the ghastly smell, are still there, a permanent fixture of our culture.

Google satellite view of Neville Chemical Company

Ethylene and isobutane are the two chemicals that caused such a problem in Pasadena, Texas back in 1989, when a repairman connected two compressed air hoses in a reversed position, leading to an explosion that killed 23 people and destroyed their beautiful plant. The Phillips 66 plant on the outskirts of Houston was remarkable in that, somehow, they had managed to get some bushes and grass to grow in front of it, something the factories in places like Niagara Falls, New York never accomplished. But of course it made no difference.

Unlike Pittsburgh, where the steel mill industrial ethos is all but gone, Texas City and Pasadena remain as beacons of how rough men (mostly) did dangerous jobs, took their lumps, built things as well as they knew how, and got covered in grease while doing so.

Those workers knew an awful lot about steel and chemicals. They gave the impression they were determined to succeed because they knew their work was important, and that made the city seem important.

These chemical plants are just as much a part of our culture as Miley Cyrus and Led Zeppelin, Frank Sinatra, and Beethoven. The difference is that, unlike our entertainment culture, our industrial and engineering culture all serves a practical purpose. Unlike the sequences of notes in music, each component has a meaningful, physical function. The reactions among these molecules are a part of Nature that we've been wrestling with since our first encounter with the saber-toothed tiger, and sometimes we still get bit.

The residents of Ben Avon, a once ritzy neighborhood on a hill that overlooks Neville Island, live downwind of Neville Chemical Company and the Petroleum Products Corporation oil storage facility, and they might not share our romantic view of its grimy cultural ambiance. To them the chemicals in the air just make the paint peel off the wall. But to the rest of us there is something magical about a maze of steel pipes, valves, and storage tanks. Instead of the illusions of TV and the stage, they show us the truth of how the world works.

Some argue that lack of intrinsic meaning is the defining characteristic of culture. In a decadent society, once a technology becomes obsolete and ceases to have intrinsic value, it becomes interesting as an object in itself. Doing gradually changes into thinking about doing, as our rusting industrial facilities change into objects of nostalgic reflection and sadness, sometimes amusement, and sometimes grief.

But to the engineering mind there is beauty in something that is functional, efficient, and intrinsically meaningful. The functionality and the industrial scale create a sense of awe.

We may be losing that sense of awe, but our culture retains traces of it. We should try to hang on to it. Though sometimes ignored by the entertainment media, science and technology define our civilization. The petrochemical industry's technology is fascinating and underappreciated. They should give tours. Well ... on second thought, maybe not.

1. The Universal Oil Products (UOP) Penex process uses a chlorided alumina type catalyst, according to Honeywell. See also Platinum Metals Rev. 3, 9–11 (1959).

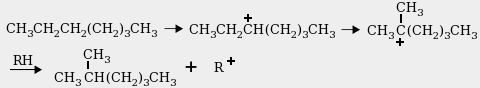

2. The isomerization reaction is an acid-catalyzed rearrangement like this

one that converts n-heptane to 2-methylhexane through a carbocation intermediate

and a 1,2-methide-hydride shift:

Disclaimer: I have no connection with the petrochemical industry.