ere's an

article

on face masks that mentions a big problem in science: what to do about

weak papers that don't actually answer the question they're studying.

The author, Cathleen O'Grady, asks whether weak health studies can do more

harm than good and can produce ‘misinformation’, or

whether many small COVID-19 studies accumulate into a clear picture over time.

ere's an

article

on face masks that mentions a big problem in science: what to do about

weak papers that don't actually answer the question they're studying.

The author, Cathleen O'Grady, asks whether weak health studies can do more

harm than good and can produce ‘misinformation’, or

whether many small COVID-19 studies accumulate into a clear picture over time.

She's firmly on the side of ‘misinformation’, but weak studies are the bane of every research scientist: you come up with a brilliant new idea, start planning a study, and discover that someone else has already published a badly-done experiment and gotten a result that is not credible.

The existence of a shit paper is a problem. You'll have trouble publishing your results because the reviewers will just say they're not new. If you confirm their results, the credit goes to somebody else. If you don't confirm them, the reviewers will say it contradicts what's in the literature. All you can do is forget the idea and do something else.

Face masks for COVID

You might remember that a couple years ago there was this big disease called COVID, and we all had to wear masks. The Science editorial mentioned a randomized trial in Denmark with 5000 people, called DANMASK-19 [1], which was criticized by Haber et al. [2] for being “uninformative.” It was not. The DANMASK abstract is pretty clear:

The recommendation to wear surgical masks to supplement other public health measures did not reduce the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate among wearers by more than 50% in a community with modest infection rates, some degree of social distancing, and uncommon general mask use. The data were compatible with lesser degrees of self-protection.

They reported that the effectiveness of masks was somewhere between +46% and −23%. This tells us something useful, namely that there's a huge amount of noise in this system. It also set upper and lower limits for what masks can do: they cut infection rates by no more than fifty percent. Haber says this “invites misinterpretation, particularly with regard to fallacious interpretation of statistical insignificance.”

Here's an example of what he's talking about: a respected website titled their article “New Danish Study Finds Masks Don't Protect Wearers From COVID Infection.” That's apparently an exact quote from a similar New York Times article. Whatever the Times wrote originally, their article is now titled “A New Study Questions Whether Masks Protect Wearers. You Need to Wear Them Anyway.” It's not only just as inaccurate but also adopts that trendy two-sentence style that drives people up the wall.

Maybe Haber et al. are trying to say they don't trust the news media. If so, they can join the club. Or maybe they have unpublished results of their own that conflict with it. If not, their criticism makes little sense.

The main criticism of DANMASK-19 seems to be that they didn't have a big enough population to see the effect. That's the thing about population statistics: with a big enough number of subjects you could prove that holding a Bible in front of your face would protect you. Then we'd get people demanding an even bigger study of whether holding up a copy of The Truth About Masks by Judy Mikovits protects you more than The Mask of Fu Manchu. Better yet, hold up a copy of the Malleus Maleficarum, thereby ensuring that you also benefit from social distancing.

The fact is, if someone tells you “masks work” or “masks don't work” without specifying numbers, they are making a meaningless and unscientific statement. Nothing is absolute in science.

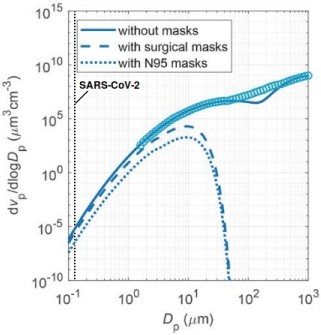

Graph from Cheng et al.[6] showing the ability of masks to absorb particles of different sizes after sneezing. This volume size distribution graph describes the concentration of particles per cubic centimeter as a function of particle diameter. The authors say that open circles are measured data. The graph shows that the efficacy of different masks changes dramatically with particle size. Most particles in a sneeze above 30 μm in diameter are caught by either type of filter. Bare SARS-CoV-2 particles are about 0.125 microns in diameter, close to the left-hand edge of the curve, where surgical masks don't catch them. This means that the effectiveness of a mask depends on the virus's level of hydration

The quality of research on anything related to COVID has been generally poor, and that includes masks. One study [3] used a web-based survey to claim that a 10% increase in mask wearing tripled the likelihood of stopping community transmission. This is a highly questionable result and it's something most scientists would not bother to read, let alone publish. And what to make of this:

During past national crises, persons in the US have willingly united and endured temporary sacrifices for the common good. Recovery of the nation from the COVID-19 pandemic requires the combined efforts of families, friends, and neighbors working together in unified public health action. When masks are worn and combined with other recommended mitigation measures, they protect not only the wearer but also the greater community. [4]

The question of how well masks can block the virus belongs to science. When they start talking about “sacrifices for the common good” they're no longer doing science, but activism. Skeptics can smell activism a mile away, and they will assume the reason we have to use language like that is that we're lying to them. That's a far more serious danger to science than weak studies.

As an aside, maybe what we really need is a mesh of ultraviolet LEDs, or a mask containing immobilized ACE2 proteins, or better yet a mask with an electric corona discharge to sterilize the air we inhale: a bug-zapper for the face. Sounds crazy? Somebody in Saudi Arabia [5] is building one.

I could only find one article on this miserable subject that adopts a scholarly level of inquiry: a theoretical study by Cheng et al.[6] They found what we already knew: surgical-type masks allow between 30 and 70% of the particles to get through—averaging 50%, remarkably close to the Danish study. Whether that's what you want depends on how many virus particles are around. In a hospital, masks are more effective, but there are also many more virus-containing droplets, so anything less than an N95 still gets you sick. In conditions of low virus abundance, there is a benefit, albeit a modest one. Their graph (shown above) shows why it's so hard to get a definitive answer: it depends on the particle size. And as I calculated back in 2020, that depends a lot on the humidity.

In the graph, the y-axis is particle concentration in air (measured by volume instead of, say, mass) as a function of particle size. Particles start out big when they're sneezed and shrink rapidly by losing water, especially if the humidity is low. Even though most of a sneeze consists of droplets >5 μm, these big droplets contain few viruses. Most viruses are in the smaller droplets (fine aerosols). The big droplets are easily absorbed by any mask, while smaller ones are not. Thus, whether a mask blocks a particle efficiently or only partially depends on how much water the original droplet has lost, which depends in turn on its surface properties, the distance it has traveled, and the relative humidity.

Because aerosol particles are so much harder to stop with a mask after they've shrunk in size, it's more effective for a sick person to wear a mask than for a bystander. At least, that's the theory. Throughout the paper, the authors repeatedly assure us that masks really really do work, as if terrified of being accused of saying something contrary to the narrative.

So in short, we're shooting down a clinical trial that tells us something we don't want people to hear, and we're forced to fall back on a theoretical paper that tells us the same thing, but says it in a more indirect and complicated way. And we wonder why the public is becoming mistrustful of science.

1. Bundgaard H, Bundgaard JS, Raaschou-Pedersen DET, von Buchwald C, Todsen T, Norsk JB, Pries-Heje MM, Vissing CR, Nielsen PB, Winsløw UC, Fogh K, Hasselbalch R, Kristensen JH, Ringgaard A, Porsborg Andersen M, Goecke NB, Trebbien R, Skovgaard K, Benfield T, Ullum H, Torp-Pedersen C, Iversen K. Effectiveness of Adding a Mask Recommendation to Other Public Health Measures to Prevent SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Danish Mask Wearers : A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2021 Mar;174(3):335-343. doi: 10.7326/M20-6817. PMID: 33205991; PMCID: PMC7707213.

2. Haber NA, Wieten SE, Smith ER, Nunan D. Much ado about something: a response to "COVID-19: underpowered randomised trials, or no randomised trials?". Trials. 2021 Nov 7;22(1):780. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05755-y. PMID: 34743755; PMCID: PMC8572532.

3. Martí M, Tuñón-Molina A, Aachmann FL, Muramoto Y, Noda T, Takayama K, Serrano-Aroca Á. Protective Face Mask Filter Capable of Inactivating SARS-CoV-2, and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Polymers (Basel). 2021 Jan 8;13(2):207. doi: 10.3390/polym13020207. PMID: 33435608; PMCID: PMC7827663.

4. Brooks JT, Butler JC. Effectiveness of Mask Wearing to Control Community Spread of SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2021;325(10):998\u2013999. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.1505 Link

5. El-Atab N, Mishra RB, Hussain MM. Toward nanotechnology-enabled face masks against SARS-CoV-2 and pandemic respiratory diseases. Nanotechnology. 2021 Nov 19;33(6). doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/ac3578. PMID: 34727530.

6. Cheng Y, Ma N, Witt C, Rapp S, Wild PS, Andreae MO, Pöschl U, Su H. Face masks effectively limit the probability of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Science. 2021 May 20:eabg6296. doi: 10.1126/science.abg6296. PMID: 34016743; PMCID: PMC8168616. Link (Note: supplementary materials are repeatedly cited in this paper but the link on Science's website does not work)

dec 05 2021, 1:47 pm. last updated dec 09 2021, 6:35 am