very so often, when I get really bored, I take a look at the psychology

literature. It's a great source of entertainment, and highly recommended,

as it's good for your brain in much the same way that roughage is good

for your digestive system.

very so often, when I get really bored, I take a look at the psychology

literature. It's a great source of entertainment, and highly recommended,

as it's good for your brain in much the same way that roughage is good

for your digestive system.

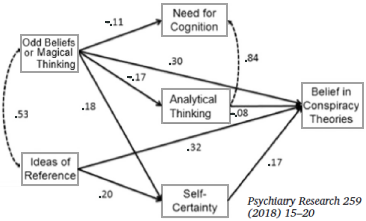

Here's an example: in an article in Psychiatry Research[1], six psychiatrists claim to have discovered an association between analytic thinking, cognitive insight, and belief in conspiracy theories:

[T]he cognitive disorganisation and possible delusional ideation that is typified by high scores on [tests of] Odd Beliefs and Magical Thinking is associated with lower tendencies to process information analytically, which in turn leads to greater assimilation of conspiracy theories.

Conspiracy theories are a big topic these days in psychology. One common trait of conspiracists, it's thought, is that they all show signs of ideas of reference, which are beliefs that events in the world relate directly to you, such as being paranoid or believing you're on a mission from God. The authors say 55% of US adults believe at least one conspiracy theory. The general idea in the paper is that everyone previously assumed that schizotypal personality traits caused belief in conspiracy theories, but now they know it's not so simple: self-certainty is also involved because it prevents reflection.

As in much of psychology, there is insufficient orthogonalization going on here: isn't a conspiracy theory itself an ‘odd belief’? Aren't conspiracy theories all paranoid? What they've really proven is that A is significantly correlated with A.

Conspiracy theory diagram from the paper. Numbers are correlations (r values). All r values are p<0.05. r values above .0.15 are p<0.001. Pathways without arrows were not significant. Redrawn from [1]

It's food for thought, though most scientists would be suspicious of any r values this low. But stepping back, how do we even know whether we believe something? It's not as clear-cut as you might think.

The question comes up a lot in thinking about religious beliefs. Do people really believe the transubstantiationist idea that wine literally turns to blood? What about other traditional beliefs, like reincarnation or the existence of the Hindu god Shiva? As philosopher A.C. Grayling says[2], people have a fuzzy concept of what God really is. But if you don't know what something is, how can you be sure you really believe in it? Maybe sometimes belief doesn't enter into it at all, and much of it is just a wish to participate in traditional beliefs and communal ceremonies.

The question also comes up in discussions of climate catastrophism, which as many have pointed out has turned into a religion. ‘Pointing out’ might not be the right phrase. Everyone on the planet, including me, has been screaming it from the rooftops for years. It has all the signs of a dangerous cult: fanaticism among the young, insistence that things taken on faith are unquestionable and that unbelievers are a threat, hostility towards opposing beliefs, self-certainty, harshness toward apostates, and a preference for emotions over analytical thinking.

Christianity has the doctrine of double effect, proposed by Aquinas, which says it is permissible to harm someone as a side effect, but not as a means of achieving a greater good. This doctrine is also clearly evident in catastrophism, with many saying that unbelievers should be imprisoned, silenced, put “up against the wall,” or even eaten.

From the aforementioned psych paper, we can consider that ideas of reference and magical thinking also play a role. But this is only true if they truly believe what they're saying.

How do we know when we believe something?

There's a dispute among psychologists as to whether religion is an adaptation for cooperation, which is to say a way of codifying norms of good and bad behavior, or whether it is a maladaptive meme. In an influential paper,[3] Pyysiäinen and Hauser acknowledge that the definition of a religion is fuzzy, but they claim that religion evolved as a cognitive byproduct of pre-existing cognitive capacities that evolved for non-religious functions:

Religion stands on the shoulders of cognitive giants, psychological mechanisms that evolved for solving more general problems of social interactions in large, genetically unrelated groups.

Catastrophism too stands on the shoulders of pre-existing psychological giants. Belief in climate catastrophism, like religion, gives meaning to a believer's life. It provides a ready-made explanation for almost every problem. It has recently mutated into a conspiracy theory about the oil companies, and it codifies norms of good and bad behavior, such as the need to minimize one's “carbon footprint.” But is it a genuine belief or a stalking horse for something else?

Belief rituals tell us the answer. In traditional religions, belief rituals serve as signals of commitment to the group. They serve to identify true believers as those who engage in costly displays of commitment such as giving time and money, proselytizing, and undergoing hardship in rituals. A ritual is defined as a symbolic act with no practical benefit. The ritual of turning the lights off for one hour on Earth Day is a perfect example. The more costly the act, such as shutting down the electric grid, the more it is taken as a sincere belief. Conversely, building an ocean-front house while proclaiming a belief in rising sea levels is likely to be interpreted as trying to reap the benefits of belief without actually believing.

The ultimate display of commitment is martyrdom, as some catastrophist fanatics have claimed to be doing when they starve themselves to demonstrate their commitment. But how to distinguish this from emotional blackmail? Both are public displays intended to sway the beliefs of others by signaling strong commitment to the ideology.

The difference seems to be that a martyr's hardships are imposed by others. The martyr has not imposed the hardship on himself; he is just refusing to yield. The child threatening to cut school, starve himself to death, or hold his breath until he dies is just blackmailing you. Maybe that is what distinguishes a cult from a real religion.

We could also suppose that pre-existing beliefs are protecting factors. An obvious one is experience in the hard sciences or in dealing with physical objects, where one learns to distinguish real patterns from social constructs. Another would be a conventional religious belief. Believing in two different religions at the same time would require vastly greater displays of commitment than believing in just one. This might explain why conservatives, who are more likely to have real-world experience and to believe in conventional religions, are less likely to believe in climate catastrophism. Only when the cost of belief is small is it possible to belong to two religions, and in such cases the authenticity of the person's belief is easily called into question.

If our civilization survives the catastrophists, future sociologists will learn much about how religions can start from ordinary, benign beliefs. Science evolved in part as a way of escaping the confines of religious dogma. It is ironic that it is now creating new ones.

1. Barron D, Furnham A, Weis L, Morgan KD, Towell T, Swami V. (2018). The relationship between schizotypal facets and conspiracist beliefs via cognitive processes. Psychiatry Res. 259, 15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.10.001. PMID: 29024855

2. Grayling AC, The God Argument: The Case Against Religion and for Humanism. Bloomsbury, N.Y., 2013.

3. Pyysiäinen I, Hauser M. (2010). The origins of religion: evolved adaptation or by-product? Trends Cogn Sci. 14(3),104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.007. PMID: 20149715 Link

jan 05 2020, 5:04 am. minor edits 12:18 pm