all (2022) was on cable this week. I'm a sucker for movies about

microwave antennas, but what a disappointment. There's almost nothing

about microwave antennas in the entire movie. I'll fix that omission

in this review by including the missing antenna details, which would

have made the movie a lot more exciting.

all (2022) was on cable this week. I'm a sucker for movies about

microwave antennas, but what a disappointment. There's almost nothing

about microwave antennas in the entire movie. I'll fix that omission

in this review by including the missing antenna details, which would

have made the movie a lot more exciting.

Scene from Fall where Becky climbs up a twenty-foot mast to charge her drone from the aircraft obstruction warning light while her friend watches. Note the absence of a lightning rod above the light

Two young women decide to climb up a 2000-foot microwave relay tower in the middle of a desert. The road is barricaded and the sign in front says DANGER: RISK OF DEATH, but nothing ever happens in a disaster movie without somebody doing something stupid. Besides, they want to drop the ashes of one of the girls' husbands off the top in a sentimental gesture. The adventurous one keeps saying things like “Life is short and you have to grab all the experiences you can,” which reminds us old folks about that beer commercial about “grabbing gusto.” (I am not watching this movie again to see if that's the correct quote, but it was something like that). If those two girls had only known all they needed to do was grab a couple cans of tasteless carbonated piss they might have had a fun day.

But nuuuuuu. They had to climb up the tower. Sure enough, a sequence of improbable events puts them in mortal peril. Passing through the cage ladder that goes only as high as the microwave dishes, they climb up past it on a rusty ladder to a sort of crow's nest. The bolts somehow come loose and the ladder collapses into the dust 2000 feet below.

Now, anyone who's ever tried to loosen a rusted steel bolt knows that's just not going to happen. You'd need an axle grinder to get those suckers loose. In microwave relay antennas, there's a thing called the “rusty bolt effect” which has to be avoided at all costs. This is because a loose connection anywhere near the antenna creates new frequencies that cause interference, putting the dish out of spec and setting the FCC after you.

For instance, if you had signals at 10 and 12 GHz, you'd get junk at 2 × 10 − 12 and 2 × 12 − 10, or 8 and 14 GHz. Since the microwaves would also be modulated, you'd have many closely spaced frequencies (12.0, 12.1, etc.) and you'd also get noise trampling all over your own digital signal.

Left: Antenna tower with no warning light photographed with a telephoto lens.* At right is a cell tower with red warning lights the same distance away. The tower is only one-third as high as the one in the movie. Note the folded dipole antennas, often used for lower VHF. They're all the same size, meaning this tower is dedicated to a specific narrow range of channels. Right: Higher zoom next day showing a vulture (a rare sight this time of year) on the tower. Crows, which are much smaller, also hang out here

But never mind, they're now trapped 60 feet above the dishes with only a 50 foot rope, two cell phones, and a flare gun with a single flare. Their drone, their water, and their all-important selfie stick have fallen and landed out of reach on one of the dishes.

The girls can't get a cell signal for some reason. They think the reason is they're too high, so they put one of the girls' phones in a sneaker and toss it to the ground, hoping it will get a connection on the way down and transmit their SOS text message to the girl's 60,000 followers. It seems not to work, and now we have to watch these two kids suffering about as horribly as you can imagine.

It never occurs to either of them to use their drone to lower the cell phone to the ground, which would have saved them. And of course they don't have a GMRS emergency transceiver on them, which also would have saved them. As would holding their cell phone near the focal point of one of the dishes: microwaves are much shorter than cell phone wavelengths, so they wouldn't interfere even if the repeater was working. Or any of a half dozen other things, like rewiring the repeater circuit to send an SOS, making sure Bluetooth and Wi-Fi are turned off (to save the battery and force the phone to use 4G LTE), splitting their 50-foot rope in half to make a 100-foot rope, or remembering Bear Grylls's advice to bring a few hundred feet of paracord with you wherever you go.

If they'd had the foresight to bring some appropriate tools, they could even have cannibalized one of the microwave antennas. According to Charles M. Kopp, who wrote the chapter on microwave relay antennas in R.C. Johnson's Antenna Engineering Handbook, those parabolic dishes typically have a forty decibel gain, which would have given them a strong signal even at Wi-Fi frequencies. It is one of the ironies in the movie that they're in a radio communications tower surrounded by high-gain antennas yet all their attempts to communicate by radio fail.

Scene from Fall where Becky's friend prepares to jump to the fifty-foot rope. Note how both dishes are misaligned. This would cause massive signal loss in an antenna with such a narrow beamwidth

Their water and drone are way down there in their backpack, so one girl rappels down the 60 foot pole with their 50-foot rope and uses the selfie stick to hook the backpack to a loop in the rope. She leaps toward the rope—still 2000 feet up—sweaty palm time—telling the other girl (Becky) to pull her back up. Unfortunately the drone's battery is now dead. But they notice a blinking red aviation obstruction warning light at the top of a 20-foot mast above the crow's nest, so Becky, calling on her vast experience with climbing up poles, climbs up the mast, pulls off the red glass filter, unscrews the incandescent light bulb, and holds her 120 volt charger, which she thoughtfully brought with her, in the light socket for what must be at least two hours in the howling wind, all the while being viciously attacked by vultures. Lucky for her the aircraft obstruction light isn't one of the new 270,000-candela strobe types. Also, luckily, she doesn't need a screwdriver to get the red lens off. And luckily the bulb takes a standard E26 socket instead of something else.

She's also lucky the tower even has a warning light. The FAA is supposed to map them, but misses a lot of them (see photo above).

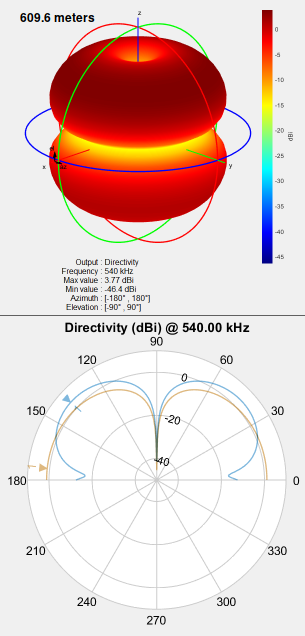

Top Radiation pattern from the antenna in the movie. Blue line

is the ground

Bottom Directivity pattern of the antenna in the movie (blue) and

a properly sized monopole (brown) at the lowest frequency in the AM

broadcast band. In this plot, 90 degrees is straight up. Most of the

energy would be beamed into space. Whoever designed this 2000 foot

antenna seems to have made many mistakes. No wonder they're planning

to demolish it

Although they call it a TV tower in the movie, it looks more like it was originally used as a medium-wave AM radio antenna. These are called monopole antennas, and they're connected directly to the ground. The radio waves are fed to the antenna at some midpoint on the antenna. This means the radio waves don't get shorted to the ground as you might think. Instead, the antenna gets tuned in such a way that the radio waves are emitted mostly from the middle of the antenna in the horizontal plane.

Tall AM antennas like this resonate at long wavelengths, where groundwave propagation is predominant, and were once common in flat areas of the midwestern US. The size of the ladder is insignificant compared to the wavelength of 2000 feet (609.6 meters). It wouldn't interfere with the radio signal; its main effect would be to slightly broaden the antenna's bandwidth.

But there's something strange about this antenna. Maximum area coverage is found from a monopole of 5/8 wavelength. Above 0.72 λ, much of the energy travels up toward space; a monopole antenna a full wavelength high emits almost no energy horizontally (see image at right). As it exceeds 1.0 λ, the pattern acquires more and more complicated lobe pattern. If this tower really is 609.6 meters high, it would work best at 975.36 meters or 307.4 kHz—way outside the broadcast band of 540–1700 kHz. To make it work, they'd have to have short vertical segments insulated from each other—a challenging engineering problem for a big antenna, which, as the movie shows, is mostly steel.

If the transmitter had been in use, the cage ladder attached to the tower would have been energized along with the tower. At the design impedance, a 50,000 watt radio signal might carry a thousand volts, and the two kids would have gotten an electrical shock. By contrast, the guy wires, visible in the movie, are usually insulated from both the tower and the ground. Viewers will note that they're attached to the lower part of the tower. This is deliberate, because it prevents them from interfering with the radio signal.

Of course, the characters in the movie know none of this. The drone now fully charged, Becky climbs back down, then gets struck by lightning and knocked unconscious. (The absence of a lightning rod seems to be another flaw in the antenna's design—Becky may have a legal case here.) When she awakes, a vulture is biting her, so she kills and eats it. She scribbles a message on a piece of paper, sends the drone on its way, and—bam—it smashes into a passing truck and is destroyed.

By now nearly a week has passed. Becky is delirious from thirst. She's having horrific nightmares about her friend being dead. Suddenly she realizes the nightmares are real and she's been hallucinating for days. So she's forced to do something unimaginably awful to survive. Read some other site if you must know what it is, but be prepared to shed tears. The voice-over repeats what her friend told her: life is short, you need to experience as much as you can. Surely by now that would be a painfully ironic message at best.

There are worse movies, I guess, like that one where a bunch of people get trapped in an elevator with Satan. This story about two likeable kids being tortured to the brink of insanity is a little depressing. I have to say, if only they had stayed home and studied the Maxwell equations—or better yet, read Johnson's book—none of this would have ever happened.

* Update, Dec 28 2024 This tower may belong to the airport, since it appears to be on or near their approach path. Assuming it's 2.5 miles away, it would be about 680 feet tall. That would be consistent with the vulture being 24 inches high. Two lattice cell towers next to it are about one third as tall.

Large airplanes fly behind it at night, apparently unconcerned. Below is a 20-second time exposure.

Airplane flying behind antenna Time exposure showing a large airplane flying on approach directly behind an unmarked antenna at night, apparently at the point where the 150-foot mast starts. In fact, the plane is nearly a mile behind the antenna, so it has at least 60 feet of vertical clearance. The plane is flying from right to left and it adjusts its altitude as it gets closer to the runway. No matter what, it would be a challenge putting a light up there. I doubt even Becky could do it.

nov 06 2024. last updated dec 28 2024