mathematics

uler's formula is one of the strangest equations in mathematics. It tells

us that there is a deep connection between exponentials and sine waves.

To many people, that seems almost magical. What does Euler's formula tell

us about the real world? And how can we understand it intuitively?

uler's formula is one of the strangest equations in mathematics. It tells

us that there is a deep connection between exponentials and sine waves.

To many people, that seems almost magical. What does Euler's formula tell

us about the real world? And how can we understand it intuitively?

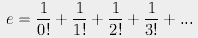

The constant e is just 2.718281828459045...

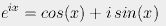

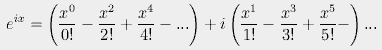

Euler's formula is

.

.

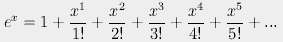

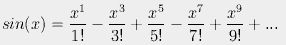

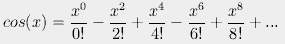

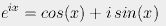

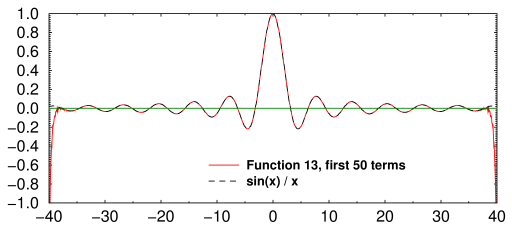

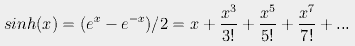

This can be proved quite easily by considering the Taylor series

expansions (named for the guy who didn't invent them)

of ex, sin(x), and cos(x):

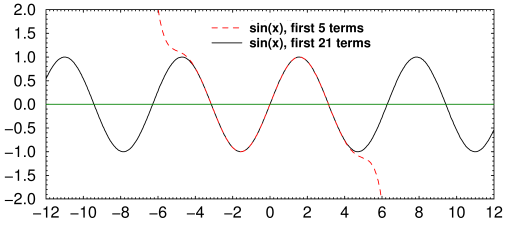

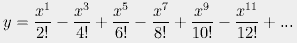

Here is an example of the expansion for sin(x) in rectilinear coordinates.

Fig. 2. Taylor series expansion of sin(x)

Fig. 2. Taylor series expansion of sin(x)

When plotted in polar coordinates, it traces out a circular pattern. Polar plots are widely used in electronics, as in the Smith chart, because they make it easier to calculate the phase that results when you do things to a sine wave. In a sense, you could think of i as a rotator: if you use i to rotate a line by π radians, you get a 180° rotation. But that would be an unconvincing and, so to speak, a circular definition. What we want to know is why.

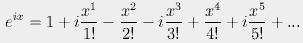

You can probably see already where this is going. All we need is some mathematical trick to change the sign of every other term in the infinite series. This is where i = √−1 comes in.

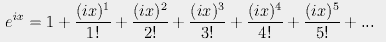

If we expand eix, we get

Traditionally, i is plotted as a y-axis, as if i were a different dimension. But that causes trouble, because i is not really a dimension. Maybe it's not fair to call i a mathematical trick, either. But whatever you call it, it's really useful.

Quantum mechanics textbooks use exponentials much more than sine functions, because they're easier to work with. As I always tell people at parties: if you don't understand Euler's formula, you will never understand quantum mechanics. You would not believe how much chicks love hearing ... hey, where'd she go?

If we set x equal to π, we get Euler's Identity:

This equation is probably as famous than Einstein's E = mc2. Every physicist and engineer learns it on the first day of class. But if you ask how it can be understood intuitively, the answer is that it can't.

What we really should be asking is: how does Nature do it? It would be nonsensical to say a photon is moving in a sine wave path; but its electric field does change in a perfect sine wave pattern. We understand from a physical point of view that this is caused by energy sloshing back and forth like energy in a spring. But why an infinite series, complete with integers?

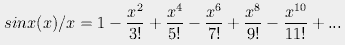

Before we get to that, let's examine what we'd get if Euler had somehow

screwed up, and accidentally used the wrong definition for i.

Suppose Euler's quill pen had slipped and he had made an off-by-one error.

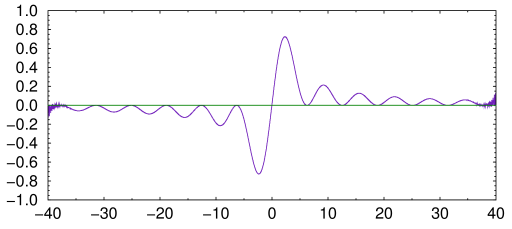

We would get the sin(x)/x function instead:

Fig. 2. sin(x)/x expansion, first 50 terms

Fig. 2. sin(x)/x expansion, first 50 terms

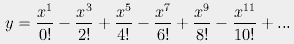

If his pen had slipped a little more, we might have gotten this instead:

Fig. 2. Function 09, first 50 terms

Fig. 2. Function 09, first 50 terms

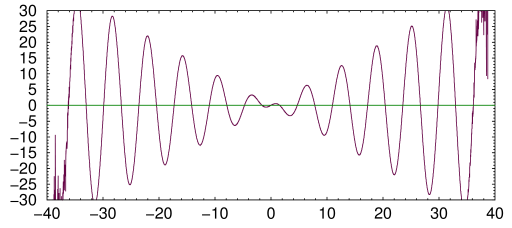

If i had been something else, we would have gotten whatever this is:

Fig. 2. Function 10, first 50 terms

Fig. 2. Function 10, first 50 terms

In fact, depending on how much you mangle the definition of i,

you can get almost any type of hump or squiggly line you want, even

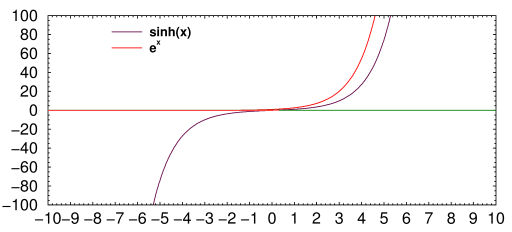

straight lines or hyperbolic sines. Here's the Taylor expansion of the

hyperbolic sine function:

Fig. 2. sinh(x) and ex

Fig. 2. sinh(x) and ex

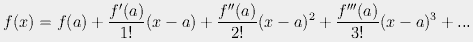

But why? Mathematically, the answer is simple: the Taylor series terms of a function are calculated from the value of the derivative of the function. Many functions have a Taylor series representation. Those that do are called analytic functions.

But what we really want to know is: do the Taylor series terms have any

physical connection to the forces acting on an electromagnetic wave? The

answer is yes. A Taylor series is just another way of representing all the

energy (and thus the forces) on a particle at some particular point, and how

it changes over time. That is, it is the sum of all the derivatives of a

function, where the first term is the function itself, the second term is

the first derivative, and so forth:

As luck would have it, the derivative of

ex is ex itself. So, for a sine wave, the

calculations are easy. The first derivative goes one way, the second

derivative goes the other way, and so forth. No wonder physicists

like them.

Another way of looking at it is to imagine raising Euler's Identity to a power.

If we square both sides of eiπ = −1 we get e2iπ = +1.

If we cube both sides we get −1 again. If we could take fractional powers,

we'd always get numbers between −1 and +1 (what we actually get is an

imaginary number off the x-axis). So we're getting a sine wave.