I was reading a book outside one cold winter afternoon when the wind suddenly blew some snow onto the book. Before I could brush it off, the snow melted and the water soaked into the pages, making them crinkly. Here's how to fix that.

Disclaimer: I am not an expert on paper. If you know of a better way to flatten paper, feel free to let me know.

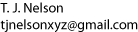

A book in a book press

- If the pages are still wet, they must be dried first by blowing with a fan, or they will stick together. Wet pages will not flatten properly because the water has nowhere to go.

- If only a few pages are crinkled, lift up the pages and place several sheets of clean paper on either side. These sheets will help absorb water which would otherwise cause neighboring pages to get crinkled. They will also prevent the metal plates from marking up the pages. Don't use paper towels—they will leave a pattern on the pages.

- Lay a 12×12 inch piece of ½-inch thick steel or aluminum plate under the pages and on top of the pages. Don't use thinner plates, or they will bend and the pressure will be uneven.

- Create a book press by clamping the two metal plates together with 6-inch clamps, using pieces of scrap wood to prevent the clamps from marking up the plates. The clamps should be about one-third of the distance from the edge. Tighten the clamps tightly. Use the heaviest clamps available.

- Allow the pages to press for at least two days.

- If the entire book is crinkled, press the whole book. Keep the metal plates away from the spine so the full pressure is on the pages. If it's a hardcover book, treat the book as in step 2, leaving the spine un-squashed.

For smaller books, you can use smaller plates and substitute a vise for the clamps. Use the strongest vise available. I can attest that both methods work. The trick is to put heavy pressure on all parts of the page; otherwise, only part of the page will be flattened and you'll have to repeat. The results are never perfect and some of the crinkling will eventually come back.

A clothes iron can remove some (but not all) of the crinkles, but it also dries the pages too much, changing the quality of the paper or making it glossy. It will also accelerate oxidation, which turns the pages yellow and brittle. If the book was printed by a laser printer, a clothes iron will melt the ink, creating a smear on the page.

Conclusion: Don't read a book outdoors while it's snowing.

Individual sheets

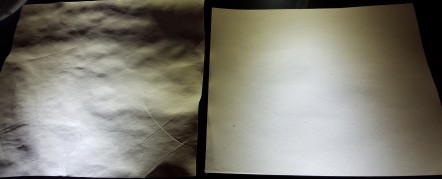

Paper becomes crinkly when it absorbs water unevenly. Logically, then, another way to flatten it would be to add water. I tested this, and it does work, but it would be challenging to flatten an entire book this way.

- Soak the page in warm water until the entire page is a uniform color with no dry cellulose, which appears as a light area.

- Lay the page down on a smooth surface such as a 1/2 inch thick metal plate. Flatten it with a non-metallic item such as a roll of blue masking tape, pressing down to squeeze any extra water out of the paper. The goal is to make the page evenly damp.

- Place a paper shop towel over it followed by a second heavy steel plate. Don't use a kitchen paper towel, or you'll get “Bounty, The Quicker Picker Upper” imprinted on all your pages. Clamp the plates together as before.

- After paper is mostly dry, place it between two sheets of clean paper clamp it between plates again.

- At this point the page will be stuck to the surface. Allow it to dry overnight. Don't heat it with a hair dryer; this will cause it to crinkle up again. Once dry it becomes un-stuck.

Paper smoothed by soaking and pressing. Left = untreated, Right = soaked in water and dried between two aluminum plates in a vise

This works reasonably well, though the surface is rougher than the original. Oh, I almost forgot, make sure the page was printed with waterproof ink before starting.

You might argue that it would be a lot easier just to throw the piece of paper away and buy a new one. But if the page is valuable that might not be possible. And some of us are really cheap.

Yellowing of paper

Book pages turn yellow over time because of an acid-catalyzed chemical reaction between oxygen and lignin, a component of mechanically pulped paper. Lignin contains phenols that oxidize in air over time. This produces organic acids which results in an autocatalytic reaction. In the past, the pulping process used strong acids, and traces of acid remained. But even modern acid-free paper will form acids when in contact with oxygen. Lignin is the main culprit, but cellulose in paper also creates acetic, formic, lactic, and oxalic acids as it oxidizes with age. Nitrogen and sulfur oxides in the air can also cause oxidation, as does heating.

Today, archival quality paper is treated with pH buffers to neutralize acid as it forms. Paper is also often coated using a process that may use weak acids, so technically it is not acid-free. The coating is typically a fluorescent dye that makes the page appear bright white, and improves printability. This paper could still be suitable for archiving as long as it does not contain lignin.

The lifetime of paper that is not yet yellow can be greatly prolonged by a process called mass deacidification. An interesting early method of deacidification used diethylzinc. Unfortunately, diethylzinc explodes violently on contact with air or water. A NASA deacidification plant burned catastrophically when water was pumped into a chamber that unknowingly contained hundreds of pounds of diethylzinc. Diethylzinc also doesn't work on microfilm, destroying it.

I work with diethylzinc in the lab, and it really is pyrophoric and toxic. It ignites spontaneously when exposed to air, and reacts violently with water. I strongly recommend not to try this at home.

feb 02, 2019