inding my car in the parking lot after work is pretty easy. Most nights the

fog that drifts up from the river and wafts among the streetlights is not

particularly thick. Sometimes the moon helps by illuminating the striated

clouds that slowly drift across the orange-brown rust belt sky. What helps

the most is that there are hardly any other cars still around. And more and

more often I find myself asking whether people really want us to cure

these diseases. If they did, they would never put up with this crap.

inding my car in the parking lot after work is pretty easy. Most nights the

fog that drifts up from the river and wafts among the streetlights is not

particularly thick. Sometimes the moon helps by illuminating the striated

clouds that slowly drift across the orange-brown rust belt sky. What helps

the most is that there are hardly any other cars still around. And more and

more often I find myself asking whether people really want us to cure

these diseases. If they did, they would never put up with this crap.

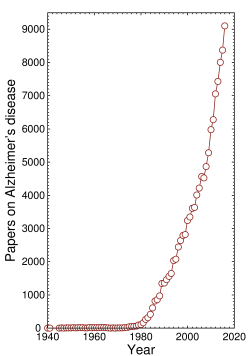

The number of papers per year on Alzheimer's disease has increased exponentially, but there is still no cure in sight. (Source: NCBI)

I don't know what biomedical science was like in the old days, but today the one thing it's not about is making discoveries. It's about getting grants. All the scientists I know are writing grants. Although they're written as if designed to find cures, that's not their real purpose. In science these days, your job is to bring in money for the university.

Take my field, Alzheimer's disease. There have been 120,913 papers on it between 1913 and 2016, maybe a million pages altogether. Assuming each paper represents, on average, two months of work for two people, a conservative estimate would be at least 120 million man-hours. Another 2,293 papers have been written in the first two months of this year. In all those 123,206 papers, not one has stumbled on a cure.

We're reporting on the results of our clinical trial next month. We'd have gotten them out last month except that my former boss insisted on including his Powerpoint presentation in the paper along with something that looked a lot like his kid's finger painting.

I should have left it in. That blob of pretty colors would probably have been the most therapeutic thing in the paper. But even though I sometimes suspected my boss of making suboptimal decisions, I can't blame him for it. The blame falls on the system that determines what we must do to stay employed.

Society is endergonic

A living creature is a society of chemical reactions. They're set up in such a way that a reaction that's needed for survival is coupled to another reaction that provides an ‘incentive’ for it, either by providing energy or by removing the end products so the necessary reaction can move forward. The technical terms are endergonic (= requiring energy) and exergonic ( = spontaneous = providing energy).

The same principle works in human societies: we incentivize raising children by coupling it to our natural desire to have sex. We incentivize economic growth by coupling it to our natural desire to become wealthy. When those connections break down, unforeseen things happen and civilization slowly starts to break down.

So it is in science. When the incentive changes, you get different results. Scientists are still motivated by curiosity, but their employment is contingent on bringing in money to pay for the parasitic administrator class, which has become the biggest population at many universities. So if you walk through a research lab today, you'll see expensive high-tech equipment. You'll see a few grad students learning how to use it. But you won't see many experienced scientists. They're all at their desks writing grants.

I came in from a nonprofit research institute. In my brief career so far in academia what has struck me most is how far universities have drifted from their original mission. Most of the people here seem to have no idea what the real world is like. They think what they see on CNN is true, and they are unimaginably naïve. I also learned that universities care only about one thing: money.

I also discovered that academics get really mad if you say this.

So many research grants, so little research

The academics tell me that, unlike in industry, everyone here cooperates freely and shares ideas openly. They all believe they're part of some noble purpose. I can't tell if they really believe that or if they're just become cynical. I'm beginning to think they're two faces of the same coin.

When you write a grant, you go to the feds, because they have most of the money. Depending on how you count—by number of submissions or by number of different grants—only 11% or 18% of grants from NIH, which is by far the biggest funding agency in biology, get funded. It takes three months to write one, so writing grants is a full-time job.

You pick an easy topic because if you go for a year or two without bringing in money and writing papers, you're thrown out and replaced unless you have tenure.

Writing a grant is a matter of trying to guess what the government wants. What you think is scientifically interesting is largely irrelevant. The requirements are mutually contradictory: the project you plan to do has to be (a) well tested, (b) new and exciting, and (c) something you've already finished doing. That's because you have to prove that (a) it will work and (b) you have the skill and resources to do it.

The only way you can prove that is to have already done it. I am not kidding about this. While reading a grant by a colleague with whose research I was familiar, I remember as I went through the list of things he said he planned to do, and saying to myself “but he did all this crap already!” The process works in reverse from what you might think: you do the work, then you get the money to do it, and you use the money to do the next thing.

I'm not implying that he was being dishonest. This is how the game is played when dealing with the government. Innovation is strongly discouraged. When the feds tried to position R21 grants for innovative projects, it failed: academics quickly realized that they still had to demonstrate feasibility, and preliminary data were still required. Since R21s bring in less money, they are generally shunned. You bring in an R01—or else.

Everyone recognizes that change is needed. But the people with the power to change it are afraid to. So the system slowly grinds on, spending tens of billions of tax dollars and producing 1.6 million papers every year. The administrators and bureaucrats get rich, and the faculty, being smart, resign themselves to the fact that their job is to get money from the government.

I'm not complaining. My plan is to test my idea, write a few more papers, and then retire. Maybe I'll set up a lab in the basement and start those reanimation experiments I've been hearing so much about. Or maybe I'll set up that radiotelescope in my back yard that I've been dreaming about. But I suspect if the patients whose loved ones are going to die knew the reason for it they'd be mad as hell.

Last edited Mar 11, 2017, 1:22 pm