Psychoacoustics:

Facts and Models, 3rd ed.

Hugo Fastl

Eberhard Zwicker

Springer, 2007, 462 pages + CD

Psychoacoustics:

Facts and Models, 3rd ed.

Hugo Fastl

Eberhard Zwicker

Springer, 2007, 462 pages + CD

ith a title like Psychoacoustics, the temptation to make jokes about

cutlery and guys named Norman is almost irresistible. But psychoacoustics

is not the study of sounds made by motel-keepers who keep their relatives

stuffed in the attic, but the branch of psychology that studies the

relationship between acoustical stimuli and hearing sensations. And like

child psychiatrists (who are always adults) and plumbers (who, contrary

to popular myth, almost never smoke plumber's crack), psychoacousticians

have by now heard all the dumb jokes about their profession.

ith a title like Psychoacoustics, the temptation to make jokes about

cutlery and guys named Norman is almost irresistible. But psychoacoustics

is not the study of sounds made by motel-keepers who keep their relatives

stuffed in the attic, but the branch of psychology that studies the

relationship between acoustical stimuli and hearing sensations. And like

child psychiatrists (who are always adults) and plumbers (who, contrary

to popular myth, almost never smoke plumber's crack), psychoacousticians

have by now heard all the dumb jokes about their profession.

The focus of this book is phenomena such as pitch strength, critical bands, loudness, and masking, in which one sound blocks the perception of another sound. There are numerous graphs and tables, mostly from the authors' own work. A handful of equations, which are empirical in nature, are also given. The hundreds of graphs show how sound perception is affected by loudness, frequency, and sound complexity.

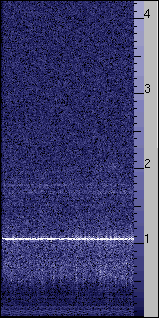

Sonogram of otoacoustic emission made by this reviewer from the CD

included in the book. This sound is a pure tone produced by the human ear.

Sonogram of otoacoustic emission made by this reviewer from the CD

included in the book. This sound is a pure tone produced by the human ear.

Perhaps the most interesting section is the one on otoacoustic emissions. Many people don't realize that the ear not only detects sounds, but can also produce them. These sounds, called otoacoustic sound emissions, can be single pure continuous tones (see image at left) or delayed "echoes" (up to 20 msec) of particular frequencies of an incoming sound. These sounds are quite low in intensity, well below the threshold of human hearing, which is about 0 dB sound pressure level. (Bear in mind that on the decibel scale, absolute silence is not zero but minus infinity.) Otoacoustic emissions have no relationship to the sounds heard during tinnitus.

The existence of ear-generated sounds indicates that the ear uses some sort of active acoustic amplification process that may account for its high sensitivity. Even without active processes, the human ear can easily hear sounds of 60 decibels, which corresponds to a displacement of less than the diameter of a single atom. Active processes increase the sensitivity to allow hearing of sounds 30 dB (1000 times) fainter.

The CD contains a recording of an actual otoacoustic emission, which alone is almost worth the price of the book, which is substantial. The rest of the CD demonstrates various types of sound masking, and is very effective at illustrating the concepts in the book.

However, I was disappointed to find that the physiological basis of these active processes was not discussed. For example, hearing loss is correlated with the disappearance of otoacoustic emissions. The reader might well wonder whether the ear uses otoacoustic emissions as a sort of regenerative amplifier. These and many other questions of a biological and medical nature (such as threshold shifts) are not addressed. Likewise, physicists will find little about harmonic oscillators, physical processes in the ear, or architectural acoustics.

Musicians, too, will be disappointed to find little information about musical acoustics. The human ear can only distinguish 640 different pitches which, if they were evenly spaced, would work out to about 44.8 intervals per octave. But what the ear perceives is not always what is there. For a high frequency tone, the perceived pitch seems to increase when the loudness increases. Meanwhile, for low frequencies, the perceived pitch decreases with loudness. On the other hand, for broadband sounds, the perceived pitch always increases with loudness, regardless of its frequency. These complicated effects can create nightmares for piano tuners, musicians, and sound engineers. The authors assume that these effects are created in the brain, similar to optical illusions with visual phenomena. But deviations in pitch could just as well be produced by nonlinearities in the ear or by neurological circuits. The authors have no comment, and stick to the narrow topic at hand. Like Sergeant Friday of Dragnet, they present just the facts. Most of the chapters are compilations of results from human subjects performing listening tasks, usually with questionnaires, in a sound booth; there is no data on evoked potentials or other physiological measurements, topics outside the domain of traditional psychoacoustics.

While I was reading this book in the shower, I also noticed a fair number of misprints and doubly-printed pages. The writing is mostly clear, considering the authors' primary language is German. It contains 60 pages of references to scientific papers, half of which are in German. The graphs are sometimes a bit confusing, with occasional unlabeled symbols, inconsistent units, and unexplained curves.

However, all Psycho jokes aside, these minor deficiencies are more than compensated by the wealth of important and sometimes fascinating data in this book, and the sharp incisiveness with which the authors repeatedly plunge into the field of psychoacoustics and stab at the boundaries of human knowledge. This book is a killer.